My photography can sometimes come in waves. At certain times of the year I may be out photographing frequently and almost constantly working on recent photographs in between the photography excursions. At other times of the year life intervenes and/or the weather doesn’t cooperate. I’ve been somewhat in the latter state for the past couple of months. I’ve still been doing a fair amount of photography, but teaching work and other distractions have also required more of my focus.

In the last few days I had an experience that reminded me of how important it is to connect to my subjects on a deeper level, and which made me feel that I was beginning to move back into that photographer state once again. It was nothing profound — simply a morning walking a different trail than the one I usually take at Muir Woods. A brief encounter with another hiker got me thinking about this way of seeing and engaging the landscape.

I saw him coming up the trail as I was stopped to make a photograph, with camera and tripod set up and a pack of other gear on my back. He was traveling light, with only a very small pack, and moving quickly. As he went by he asked, “How much does that weigh? Eight or ten pounds?” That caught me slightly by surprise, since I hadn’t really considered the weight of everything — it weight what it weights! (It is probably more like 20 pounds.) I mumbled something about “perhaps a little more,” and then thought to ask, “And you?” He mentioned that he had a very small point and shoot style camera only, and that he didn’t want to be burdened by the extra weight. I replied that I had gone through a phase like that too, at one point, so I understood where he was coming from.

I first carried cameras into the backcounty many decades ago, probably when I was in high school and certainly by the time I was in college. In my late 20s I was regularly taking very long backpacking trips and carrying a camera body, multiple lenses, boxes of film, and other gear, and recording what I saw was an important part of the experience. It continued to be so for quite a while.

Gradually something changed. As I began to feel more connected to the experience of outdoor life and travel and more and more at home in that world, the camera began to feel like an intrusion. As I hiked and backpacked and cross-country skied and climbed, the camera seemed increasingly to stand between me and that world. I loved the physical experience of moving with strength and speed and competence and a feeling of being perfectly adapted, and I had less and less desire to stop and make photographs. Over a period of years I gradually reduced the photography equipment I carried — down to one lens, then to a smaller 35mm rangefinder camera, and finally to a very small 35mm film camera that compromised image quality for size and weight. (It was, if memory serves, an Olympus Stylus Zoom 105) Ultimately, I may have done a few backpack trips where I made no photographs and perhaps even took no camera.

A part of me regrets that. I cannot go back to those times and places and experiences and make photographs of them again. And at a certain point in your life you realize that the world is a very big place and you are not going to see all of it. (One lifetime is not sufficient to know just my Sierra Nevada!) Yet another part of me does not regret that at all. I think back to certain experiences where I was completely “in the landscape” in those days, and I suspect that having a camera would have altered those experiences. Certain specific events stick in my mind: an evening in the Upper Kern Basin, sitting alone among rocks after dusk and simply “being.” A day spent wandering Pioneer Basin with friends — climbing up to a headwall ridge, traversing part of it, descending and spontaneously deciding to climb a nearby moraine, and then rock-hopping back down the valley to our lakeside camp at dusk. Lying alone in a small one-person tent in the Yosemite backcountry as a thunderstorm raged outside. Climbing Snake Dike with three friends, topping out at sunset, descending the Half Dome cable in dusk light, and stumbling blindly down the trail to Little Yosemite in darkness. Sitting for an hour or two on top of Glen Pass on my first solo pack trip.

Today I almost never go out on a trail without camera equipment, and sometimes I carry quite a bit of it. Unlike that fellow I spoke with on the trail, I’m not experiencing the physical joy of quick and efficient movement across the landscape. Actually, I might look more like I’m trudging! But, as I also realized on my little walk at Muir Woods, I most certainly do not feel like I’m encumbered. I now feel free to slow down, to stop, to listen, and to breathe the air — in ways that rarely did back in those earlier days. And I think, at least for me, that this is necessary if I am to see the potential photographs in these places I visit. So often I find myself in a place and “not seeing it.” Then I slow down and stop and look and feel… and I do begin to see photographs where earlier there seemed to be none.

Photography of the landscape, at least for me, is not just about “capturing” images of the places I visit. I can do that if I have to, but it is not very rewarding, and it rarely results in good photography. A photograph is, on some level, an expression of my relationship to the landscape, and I hope that it may tell you as much about how I see the subject as it says about the subject itself. In order for that to happen, I need to slow down and I need time to see and think

I was once quite happy to be that fellow who passed me on the trail. Today I’m quite happy to be the fellow that he passed.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | 500px.com | LinkedIn | Email

Text, photographs, and other media are © Copyright G Dan Mitchell (or others when indicated) and are not in the public domain and may not be used on websites, blogs, or in other media without advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Discover more from G Dan Mitchell Photography

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I fully agree with you Dan and Guy. Yes, visiting iconic spots is nice but the best images are those when you create a new original image, especially out of an everyday common subject. Recognizing good light and using good composition is missing from the common photographer and we won’t get into the common oversaturation of colors movement which seems to be going on in photo forums. I prefer to work slower too with my manual focus zeiss lenses and usually like to take myb time working a scene, rather than visiting many spots just forva brief time. A lot of of my enjoyment in landscape photography is just being out there soaking natures natural beauty in. Even when the weather or clouds do not end up participating in what i want to happen for my photgraphy, I still enjoy my time out there.

I can relate to the appeal of the challenge. Early on, when I was quite young, I think that understanding the gear and the principles might have been the primary appeal, though I’ve always been intrigued by the photographs. Eventually it became the challenge of seeing things as photographs. Sometimes that is quite difficult! Just this week I had a reminder of that. A half a year ago I saw something that I knew I wanted to photograph, and I could even articulate what it was (at least for the most part) that appealed to me about the subject. But after “capturing” the images, while still intrigued by them, I was unable to quite figure out how to interpret them in post.

Oddly — though it certainly has happened before — it was after I left them behind for six months and then went back and looked at them with fresh eyes that I saw how to work with them, and in a very different way than I originally imagined, but it a way that makes perfect sense now that I’ve figured it out.

Dan

Great post Dan,

Very much enjoyed reading your post. It is amazing how much we can miss when we are in a hurry. I had a friend who was new to photography that ran everywhere. He wanted to know what settings to use and wanted to get as many shots as he could. He ran and ran and ran. Sadly, he could not comprehend the need to slow down and focus on telling an emotional story with his photography. Needless to say our photography paths do not cross much anymore. I always enjoy your art Dan.

Thanks again for the great post!

Steve

Thanks, Steve.

I think that sometimes we are worried that if we are not constantly and perhaps even superficially busy that we might get bored or that we might not be accomplishing anything or that we could be wasting our time. But it is possible to get to a place where what seems like doing nothing is actually quite the opposite!

Dan

Ah, right. Too darned many Westons! ;-)

“Difficulty in making art is not something to be avoided, but something to be savored.” Or, stated another way, something to be embraced. Or, as I like to think, it often only seems difficult until you do it, at which point you cannot imagine doing it any other way.

Take care, Guy.

Dan

* “Difficulty in making art is not something to be avoided, but something to be savored.” Or, stated another way, something to be embraced. *

That was exactly my initial motivation to take up photography a couple yr after graduating high school. I’d been a pretty decent student of ‘the 3 R’s’ as a kid, was just barely good enough at sports to not embarrass myself, but anything ‘creative’ was just absent. The only ‘artistic’ sense (if it can even be called that) I’d displayed as a youngster was doodling the Flintstones characters while watching the tv show. Music and the written word were every bit as cryptic to me as a foreign language.

And though I don’t recall what was the specific trigger that motivated me to purchase that initial Minolta SRT-101, it was definitely the challenge of something I intuitively knew I was going to find difficult to do well that drew me to it, and would be something I ‘knew’ I’d enjoy. For a rather lazy-minded, easily bored kid, that was a sliver of mental acuity I did not often display.

Of course, I still enjoy making images as much today as the very first rolls of Kodachrome I shot on the SRT-101. And I still find the making of images particularly interesting because it remains as much a challenge to do well today as it was ‘back in the day’. And every now & then, I think I get lucky.

I can relate to the appeal of the challenge. Early on, when I was quite young, I think that understanding the gear and the principles might have been the primary appeal, though I’ve always been intrigued by the photographs. Eventually it became the challenge of seeing things as photographs. Sometimes that is quite difficult! Just this week I had a reminder of that. A half a year ago I saw something that I knew I wanted to photograph, and I could even articulate what it was (at least for the most part) that appealed to me about the subject. But after “capturing” the images, while still intrigued by them, I was unable to quite figure out how to interpret them in post.

Oddly — though it certainly has happened before — it was after I left them behind for six months and then went back and looked at them with fresh eyes that I saw how to work with them, and in a very different way than I originally imagined, but it a way that makes perfect sense now that I’ve figured it out.

Dan

It was actually Brett Weston.

As you already know I share the same appreciation for these experiences as you do. This is where I often make the separation of “what’s in it” for the viewer vs. the photographer. Here’s the awkward truth: making visually appealing photographs is easy, and keeps getting easier. Too many such images are made by people going to already well known and well photographed places, or applying tried and true techniques proven to elicit favorable response. These photographers often are not even aware of how much more they may get from the practice. As observed by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi:

“The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

Those tempted by the ease of making beautiful/popular images often miss this point entirely. Difficulty in making art is not something to be avoided, but something to be savored.

Having gone through some of these phases, myself, I think that your last line is the most important, Dan. Be happy with what you do and how you do it. That’s it. There is no one formula for how to get there.

The connection with the landscape, for me, is immensely important, but I know some very good landscape photographers who never camp and rarely hike considerable distances, and they are also content with their methods as I am with mine. I know photographers who prefer to spend hours in the darkroom, and photographers for whom every moment indoors is torture. I know photographers who still haul 8×10 kits and photographers who are perfectly happy with just a phone camera. What matters is not how much your gear weighs but how conducive it is to working creatively and making the kind of work you find rewarding.

We are each different. We each find different things interesting and meaningful. The most important kind of creative work, is my mind, is that which reflects the unique sensibilities of the person behind it. The real mistake is to try to act like someone you are not, whether in order to impress others or because you think there is only one “right” way to do it. There isn’t. That’s the beauty of it.

“Without freedom, no art; art lives only on the restraints it imposes on itself, and dies of all others.” -Albert Camus

Guy, thanks for your comment — and for reminding me how hard it is to write clearly and without ambiguity!

I can see how this piece could be read to suggest that a wilderness experience is necessary for good photography. That experience is important to me, both in terms of how I see the world and in how the non-visual experiences inform my way of seeing. However, I also know wonderful photographers who produce beautiful and revealing work in the natural world who do not backpack or spend long periods of time away from roads.

(Many people mistakenly think that Ansel Adams made most of his famous and iconic photographs “in the back-country.” He made some that way, mostly quite early on, but many were made close to roads. And wasn’t it Edward Weston who famously said something along the lines of, “There’s nothing worth photographing more than 500 feet/yards from the road.”?)

I think that the point I probably actually wanted to make was one about slowing down and knowing the subject more deeply than just “what it looks like.” No generalization always holds true, and it is certainly possible to come upon something and quickly make an effective photograph of it. But when I/you/we build a good portion of our work around a particular sort of subject matter, it seems important, both personally and to the quality of the work itself, that it be built upon and present a deeper knowledge of that subject than what can be seen through a “quick glance.”

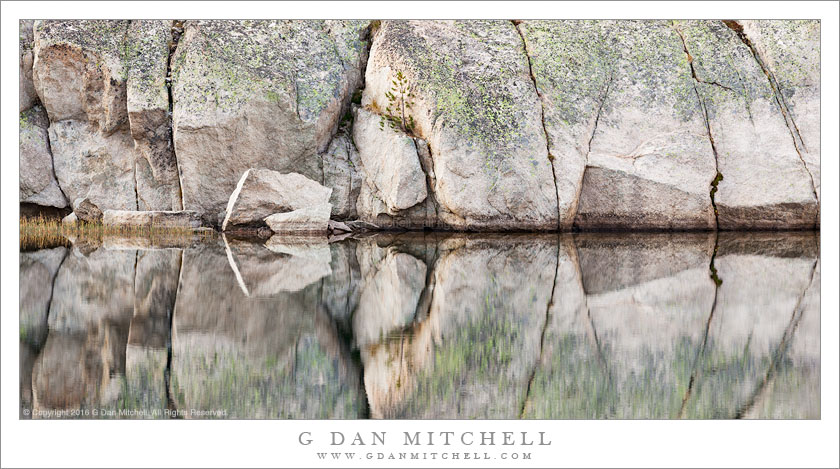

For me this means several things about the photographs. They are not just photographs of things. They are informed by a deeper knowledge of and experience with things that may not be visual at all. A photograph of granite may, for example, suggest something of the feeling of granite and a photograph of water might suggest something of its sound. This may well not be a concrete thing in the image, but the experience of those things, I think, leads to a different way of photographing the subject. And a relationship with the place/subject can also permit the photographer to reveal more than the objective features of the thing, and begin to reveal a point of view about it and a way of seeing it that is unique. Beyond that a photograph also has the potential to evoke thoughts of the non-visual sensations associated with the subject or at least imaginations of what they might be.

It is also important to acknowledge that some photographers who have been at this for a long time may be drawing on past experiences that are well enough embedded in their subconscious that they can call them up more quickly. I like to point out that when I first began to backpack it took me as long as a week to get into that special and rare state of mind that can come when you are in such places, but that after doing that sort of thing for many years I found that I could enter that state in, oh, about five minutes under the right circumstances.

But a key characteristic of that state is a slowing of the mind and body combined with a heightened awareness of things that would otherwise not be seen or felt.

Dan