I recently received an email from David, who has some questions about depth of field:

As you have a lot of experience of using the Fuji X-E1, may I please ask you for some advice regarding landscape focusing.

My aim is to use the 18-55mm kit lens with the majority of shots taken at the widest end. I have in mind setting the lens at Hyperfocal distances, based on a crop factor of 1.5 and a circle of confusion of 0.02. I think the first figure is reliable, but I’m not sure about the second in relation to the X-E1 – perhaps you could confirm.

I have already done some testing at home using the attached table (which come from the well respected DOFmaster site).

In my experiment I carefully measured distances at apertures of f8 and f11 using a tripod and a printed card as the subject. I set the lens manually at the hyperfocal distance, using the EVF distance scale. I was disappointed to find that the closest point of focus was not as sharp as I had hoped. Have you any idea why this may be?

I did a further test on aperture f11 and this time set the distance scale at 4 feet (2/3 of the way between 3 and 5 feet). This resulted in a sharp image from 3.5 feet. This would suggest that the distance scale is not accurate.

Any suggestions you have to overcome the problem would be much appreciated.

Let me preface my response on the depth of field (DOF) issue by congratulating you for taking the time to conduct your own experiments. One of the great things about digital cameras is that we don’t have to trust what we read — we can easily and quickly conduct the experiments ourselves. In addition to getting the answer to the question at hand, we end up knowing our gear at a much deeper and even intuitive level, which is extremely important when we are in the field and we don’t have time to ponder and calculate, but must instead make a photograph in the moment.

The rest of this post is going to be somewhat involved, so let me share a quick thought right at the beginning:

The usefulness of DOF calculators is very limited, as they are based on subjective assumptions that may not match what you are doing with your photographs. The best way to align your expectations with exposure choices is to test them yourself and evaluate images in the form that you most often produce — and not just at 100% magnification on a computer screen.

What is DOF? Essentially the depth of field is the distance range in front of and behind (unless you focus at infinity) the focus point within which subjects are likely to sharp enough to seem in focus when the photograph is viewed at some arbitrary magnification. This size of this range increases as we stop down (for example, going from f/2.8 to f/8 expands the DOF) and decreases as we open the aperture (going from f/8 to f/2.8 contracts DOF). This is a source of creative control for the photographer. A smaller aperture can allow subjects across a greater distance range to appear relatively sharp, while a larger aperture can keep the primary subject in focus while pleasingly “un-focusing” elements in front of and behind the primary focus point.

With this in mind, it is no surprise that photographers are often concerned with the specific effect of various apertures on DOF. For example, when shooting a scene that includes a primary subject and secondary subjects that are closer and further away, we may want to select an aperture that will make all three appear sharp enough — or we may want to select one that only leaves the primary subject sharply delineated.

I’m not a big fan of so-called DOF calculators, whether they are the old printed version or the newer software versions. For those who may not know, DOF calculators purport to tell the photographer what aperture to use to achieve a given depth of field using a particular focal length lens, and at what hyperlocal distance to focus. (The hyperlocal distance represents a point between the closest and furthest subjects you want in sharp focus — the idea is that you focus on that point and then stop down far enough to include those near/far subjects in good focus.)

The problem is that DOF is a very complex and subjective thing — not a simple binary that says that DOF is either enough or not enough. The predictions made by DOF calculators are based on a set of assumptions that may or (more likely) may not be accurate or relevant. For example, the original DOF calculations were based on relatively small image magnifications, such as an 8 x 10 print. (Even earlier they were based on contact prints made from very large negatives!) What you do with your photograph is likely quite different, and could range from displaying small images on low resolution of electronic screens to producing very large prints. The effective DOF is very different in these various scenarios.

Since the DOF calculations purport to tell us the aperture at which objects within a range of distances from the camera will be “sharp,” we have to ask, “What does sharp mean?”. The answer is a bit messy. Essentially sharp means, “not so fuzzy that we notice the fuzziness in a print of a given size.” The only place the image is actually “sharp, “or as sharp as it can be, is precisely in the (more or less) plane of focus. No matter what aperture we use, subjects that are not in that plane are not in optimal focus, and they are less sharp. DOF predicts the distances from that plane at which the softness will not be objectionable at a specific image magnification under typical viewing conditions.

Let’s consider how fuzzy (sorry, bad pun!) that concept is, using a couple of real world examples.

Most photographs made today will never be magnified much at all — they will be viewed on relatively small electronic screens that generally do not have very high resolution, at least not in comparison to photographic prints. The “not so fuzzy that we notice it” standard here is far lower than that of the DOF charts, and in a small web or email image we are unlikely to even notice softness that would have been significant in even a modest sized print. You essentially may get more DOF than the calculator predicts.

On the other hand, photographers using digital cameras to produce very large and high quality prints often magnify the source images (in your case a very small APS-C format) to an extraordinary degree, far beyond what anyone would have contemplated doing with film. It was rare to print 35mm film images beyond 8 x 10 or perhaps 11 x 14 size, but today careful photographers may produce prints at 30″ x 45″ or even larger from an originals that were captured on a surface of the same size as the 35mm negative. When we do this, tiny artifacts in the original image become much more significant, and here we might find that something predicted to be sharp by a DOF calculator is simply not sharp enough — e.g. you get less DOF than the calculator predicts. The online calculator you mentioned vaguely acknowledges this by suggesting that you might want to stop down by one stop from what the calculator suggests.

If your camera seems to produce images that are “soft” even when the subject is within the supposed DOF range, this is not evidence that your camera or your lens has a problem. In fact, it is virtually certain that the equipment is working very well. The writer’s XE1 camera and 18-55mm lens can produce excellent images, and I regularly print images from such equipment at 18″ x 24″. Instead, you are looking very closely at the image, using a high magnification, allowing you to find softness that would not likely be visible even in a 20″ x 30″ print.

Will you print that large? If so, you’ll want to change your assumptions about what apertures will work for you, stop down more, and/or consider other ways to get greater depth of field. If you won’t print that large, inspect images in your typical manner of display and consider how the DOF calculations work out in images at that size.

I never use a DOF calculator in my landscape photography. (Actually I don’t use one for any photography, and I do not personally know any other serious photographer who uses a calculator.) How do landscape photographers deal with the issues of DOF?

- Frankly, in many cases photographs use a “seat of the pants” approach. This surprises people who imagine that every photograph is carefully calculated and worked out, but the truth is that a lot of the decisions are instinctive and intuitive or based on actual observation in the field. I’ve observed that many photographers lean toward using three apertures. If DOF isn’t an issue they tend to shoot at some middle-of-the-road aperture, which might be in the f/5.6-f/8 range. If they want to narrow the DOF they tend to shoot wide open or close to it. If they want to expand the DOF they tend to shoot at the smallest aperture at which they feel diffraction blur won’t be a major issue.

- They use live view or make test exposures and inspect them at higher magnifications. I rarely use my Fujifilm camera for landscape, but on the camera that I do use for landscape I almost always shoot in “live view” mode. I manually focus on a primary subject at 10x magnification, and then I inspect secondary subjects on the screen with the DOF preview button pressed so that I can directly verify their sharpness.

- Focus bracketing is an option if you need very deep DOF and are using a tripod. Make two or more exposures at closer and further distances and then combine the sharp portions of the resulting images in post. (There is software that can help with this, though it can be done directly in a program such as Photoshop.)

- Use a tilt/shift lens to control the angle of the plane of optimal focus. Unfortunately, perhaps, this is not a realistic option on the Fujifilm cameras.

- Some photographers use a rough field technique for estimating DOF. Using live view they focus on the closest subject and note the position of the focus ring. Then they focus on the furthest subject and again note the position of the ring. Then they rotate the focus ring half way between the two points. If there is a DOF scale on the lens they use the aperture that includes the near and far distances or perhaps one stop smaller.

- Recognize that sometimes the secondary subjects can be in slightly less than perfect focus, since viewers are generally paying the most attention to the primary subject, and accept a slight softness of the image elements that are not in the plane of focus.

Almost all photography decisions involve balancing compromises among several parameters, and DOF is no exception. There are the obvious effects on shutter speed and/or ISO choices, with consequent effects on the image. Less obvious is the potential effect on image resolution through diffraction blur, which you also alluded to in your note. The trade-off here is that as you stop down to expand the DOF distance range, you also begin to reduce the maximum resolution of the best-focused parts of the image as diffraction blur increases.

I won’t go into the full story here, but again it is worthwhile to do some experimenting in order to understand this effect and what the trade-offs are. I will say that some of the concerns about loss of sharpness due to diffraction blur are over-stated and seem to be based more on a theoretical understanding than on actually making photographs. In the world of real photographs, some small amount of diffraction blur is usually completely invisible in a finished print, and in other cases the advantage of increased DOF is worth accepting the truly tiny loss in maximum image sharpness.

With all of that in mind, what should you do? It is a great idea to continue to experiment and try these things for yourself, but be very careful to not lose track of their real world effect and get sidetracked by what you can find if you go searching from problems at 100% magnification on the computer screen.

Good luck!

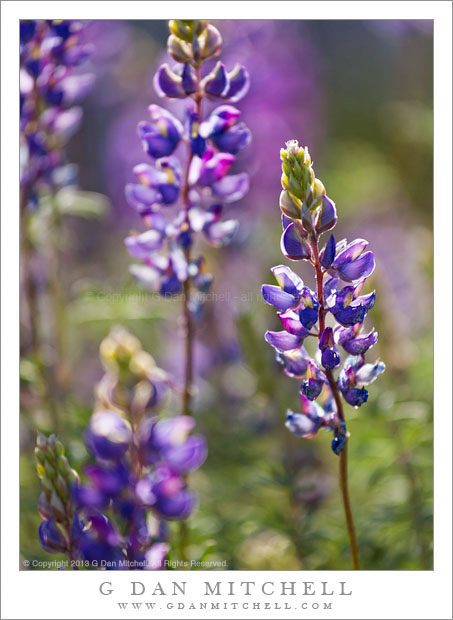

(About the photographs: I chose to include two lupine photographs in which depth of field was obviously an important consideration. The first required very large DOF, which I achieved by using a whole range of techniques: small aperture, ultra-wide angle lens, and focus-stacking. The second use DOF as much as the first, but here the DOF was restricted so as to radically soften the complex background and keep it from distracting from the foreground flowers.)

The “Reader Question” series includes periodic post in response to questions that I get via email and which I think might be useful to a number of readers.

Articles in the “reader questions” series:

- Concerned About Image Theft

- How to Add Borders to Online Photographs

- One Lens for Landscape and Wildflowers on Hikes

- Yosemite in October?

- DSLR Sensor Cleaning

- About Sharpness and Detail

- Camera Stability and Long Lenses

- Photographing in the Rain

- Landscape Lenses

- About Depth of Field

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | 500px.com | LinkedIn | Email

Text, photographs, and other media are © Copyright G Dan Mitchell (or others when indicated) and are not in the public domain and may not be used on websites, blogs, or in other media without advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Discover more from G Dan Mitchell Photography

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.