(When I started this post I thought it would be short — but it grew and grew and grew! In addition, right now and for a couple of days after the publication date, there is a Fujifilm instant rebate promotion that takes hundreds of dollars off the prices of lenses and cameras and bundles. See a list of links at the end of the article.)

My friend “Pat” sent me an email recently with the following question:

I hope you have been well. I was hoping you could offer your thoughts on ‘why Fujifilm’ for your walk-around/street photography system. I have been reading (perhaps a little too obsessively) many rave reviews on their cameras and consistently love the look of images that are shared. (Kevin Mullins, Zack Arias and many others) have professed their love for the Fujifilm system.) While my G.A.S. has been in remission lately, I know I am susceptible to a relapse-I’m not sure if I’m looking for you to talk me off the ledge or give me a solid shove. Why do you choose Fujifilm instead of using a couple of the smaller (non-L) primes with your 5D series? I shoot the 6D as my primary body and have been saving for a 24-70 f2.8 (to replace my 24-105) but the current sale on the Fujifilm at Adorama has me thinking.

As I thought about my reply it occurred to me that others might be interested in the answer, too. With that in mind, I’m sharing my reply. The main context of your question seems to be focused on street and “walk around” photography, and Fujifilm is now my primary system for what I refer to as “street photography and travel photography.”

And, yes, G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome) can afflict all of us. Let’s see if I turn out to offer an antidote… or become your enabler!

Settle back. This won’t be brief.

The Full Frame DSLR Alternative

You ask why I don’t just add a few small primes to my full frame Canon 5Dsr. At one time I took that approach. I used the Canon EF 35mm f/2 (the older model), the 50mm f/1.4, the EF 85mm f/1.8, and the EF 135mm f/2 L lenses. All of these are fine lenses and they can make for a fairly small setup, especially if you forego using the larger 135mm lens. I have done effective street and travel photography with this kind of setup, and you could use your 6D, which is smaller than my 5DsR.

Although I prefer primes for this kind of photography these days — I’ll explain the reasons a bit later — I have also traveled with just the EF 24-105mm f/4L IS, possibly augmented with a 16-35mm or 17-40mm lens. In a couple of cases, I tossed the EF 70-200mm f/4L IS into the bag as well. One interesting approach, should you decide to stick with the Canon DSLR option, could be to rely solely on the 24-105mm zoom, since it covers the same focal length range as the primes you would likely carry. It has the two downsides of larger size and smaller maximum aperture, but it has the upsides of IS, flexibility, and avoiding the need to do any lens changes.

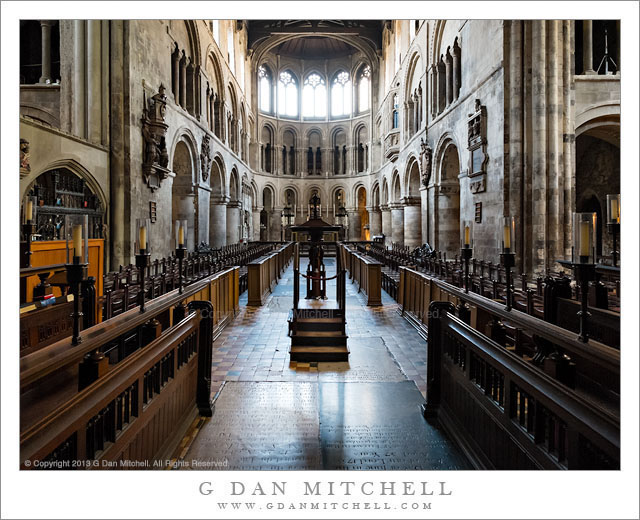

You have probably already anticipated the main downside of this equipment for this kind of photography — it is big and heavy and it shouts, “I’m a photographer!” to anyone who happens to be around. We can work quickly and somewhat unobtrusively, even with big equipment, but once it comes out it almost always distracts our subjects. In addition, carrying and managing the larger gear can make it more difficult to move quickly and fluidly through the urban environment.

One option that some like is to build a small DSLR and prime system around a smaller DSLR, such as the tiny Canon SL1. I have several photographer friends who love this system for travel photography, including my wife who does such photography using the Canon SL1 with the kit zoom, a 24mm pancake lens, and a macro. (She is largely a macro photographer.)

Full Frame Mirrorless options

Eventually Canon will have a first class mirrorless system, but today all they have is the decent but stunted EOS M system. Fortunately other manufacturers have stepped up. Sony made waves when they introduced the affordable full frame A7r, now replaced by the updated A7rII. At the time of introduction it provided a much smaller body by comparison to DSLRs, along with an excellent sensor, plus the ability to use Canon and other lenses via adapters. Downsides included the need to use those adapters — Sony introduced very few lenses — along with shorter battery life and what some describe as a less mature control interface.

Why not get the Sony? Lots of people do use it for street and travel photography, including some photographers I respect a great deal. I did not choose to go there for several reasons.

- I remained happy with my overall Canon system, and I don’t believe in “brand hopping.” For my primary photography it still serves me very well. So the other factors that enticed quite a few other landscape photographers to try Sony did not convince me. (And now my 5DsR is at least as good of a landscape camera as the Sony A7rII.)

- In addition, when it comes to street and travel photography the higher resolution of the Sony system was not a particular draw for me, nor was the larger full frame sensor. For my street and travel photography they don’t make that much of a difference. The main issue is that I shoot almost exclusively handheld when doing that kind of work, and this diminishes the potential resolution advantage of a high-resolution full frame system.

- The smaller body size was appealing — I like the look of the Sony system a great deal. But if I were to add an adapter to the Sony system so that I could use my Canon lenses, the size and weight of the overall system isn’t so impressive when using relatively large Canon lenses plus an adapter. Friends who use this approach for street photography seem to fall into two camps. One group uses some of the very nice third-party (and now Sony) autofocus primes, but they tend to be no smaller than the Canon options or even may be larger. The other group uses some very small classic film camera primes, but they are mostly manual focus lenses. My preferences is to use small autofocus lenses, and the options there were pretty limited.

I have nothing against the Sony system at all, and I believe it is an excellent one. But, as appealing as the Sony system is, I decided it wasn’t for me for this kind of photography.

Cropped Sensor Mirrorless Cameras

It turns out that there are a lot of options when it comes to mirrorless cameras using smaller sensors, ranging from the micro four thirds systems (with a 2x crop factor) through 1.6x and 1.5x cropped sensor systems. Frankly, a number of them are quite good today. How to decide?

I won’t go over the whole range of options — this post is going to be too long already without that! — but I’ll provide a brief summary. Today the micro four thirds cameras are quite good, less affected that in the past by things including ISO limits and issues with noise. The 1.6x and 1.5x cropped sensors will produce very similar results, but the more serious mirrorless systems seem to have mostly moved to the slightly larger 1.5x sensors. Given that the micro four thirds systems did not seem to provide that much advantage in size and weight overall, I gravitated to the Fujifilm’s 1.5x system.

Fujifilm X-E1

I purchased a Fujifilm XE1 near the beginning of 2013. My initial thinking was that I wanted a smaller system for some overseas travel, so I got it well ahead of time in order to run it through its paces. The primary Fujifilm alternatives to the XE1 at that time were the X-Pro1 and the X100 bodies. All are wonderful cameras, and all use essentially the same 16MP sensor. (Fujifilm’s tends to use the same sensor across their entire line, at least among cameras using the same sensor format.) 16MP is plenty for most purposes, particularly for handheld photography. I know this because I had made rather large fine art prints from earlier cropped sensor cameras and later from the 12MP Canon 5D. Here is a quick rundown of the three models at that time.

- The X100 (along with its successors the X100s and X100t) was a simple fixed lens rangefinder style camera with 23mm lenses, equivalent to 35mm lenses on 35mm film cameras or full frame.

- The X-Pro1 was an interchangeable lens rangefinder style camera that provided an ingenious hybrid optical/electronic viewfinder system. It was introduced as the high-end camera in the set.

- The X-E1 (like its successors the X-E2 and X-E2s) is a very small (almost as small as the X100) rangefinder style camera with an electronic viewfinder and interchangeable lenses.

Recently, after relying on the X-E1 for over three years, I upgraded to the X-Pro2. I’ll have more to say about that below, but for now consider it much like the X-Pro1, though with a 24MP sensor and other improvements.

I wanted lens flexibility, and I wasn’t certain that I needed the hybrid viewfinder of the X-Pro1, so I got the less-expensive X-E1. Actually, my wife and I got two of them, along with a small set of lenses: 14mm f/2.8, 35mm f/1.4, 60mm f/2.4 macro, 18-55mm variable aperture zoom, and (a bit later) the 55-200mm variable aperture zoom. Later I also acquired the 23mm f/1.4 and the 50-140mm f/2.8 image stabilized zoom.

The Early Fujifilm Experience

The bodies are small “jewel-like” affairs that remind me of vintage rangefinder cameras, though obviously updated with features and controls suited to digital camera technology. (I recall walking along a narrow backstreet in Heidelberg, Germany when a young fellow walked past, his eyes widened, and he exclaimed, “Is that a Leica?”) The XE1 is quite tiny for a full-featured cropped sensor camera, though it is not exactly “pocketable” in the way that, say, large point and shoot cameras are.

Although I had read a lot about the cameras before purchasing, I knew that I wouldn’t really understand them until I spent some time photographing with the X-E1. Almost everything turned out to be positive — some things extremely so — and only a few things were not as good. I photographed with the X-E1 for over three years, and continued to find it to be a valuable tool. I recently updated to the X-Pro2.

I have now been using the Fujifilm system extensively for about three and one half years. It is my primary tool for street and travel photography, where it has completely replaced by DSLR system. I have used it side-by-side with the full frame system when shooting certain kinds of events. (The DSLR is still my primary system, and I almost never use the Fujifilm system for landscape or wildlife photography.)

Is the Fujifilm system perfect? No. No camera system is, and I’ll summarize a few of the minuses below. Is the Fujifilm system a good a viable tool? For me the answer is an emphatic yes.

Pluses and Minuses

Here is a summary of some things that I think are notable about the Fujifilm system, with acknowledgement of both strengths and weaknesses. I’ll try to clarify which of these apply to the older Fujifilm cameras versus newer models, and which might apply to one design more or less than others

Sensor Image Quality

I am very impressed by the image quality from the Fujifilm cameras. The 16MP x-trans sensors produce very good files. Fujifilm was one of the first manufacturers to forego anti-aliasing (AA) filters on small cameras, and this enhances image sharpness with a small risk of certain image artifacts. (I have yet to see any significant problems.) 16MP 1.5x cropped sensor images are plenty good for most uses, and I regularly print at 18″ x 24″ from 16MP with excellent results — and larger prints are possible.

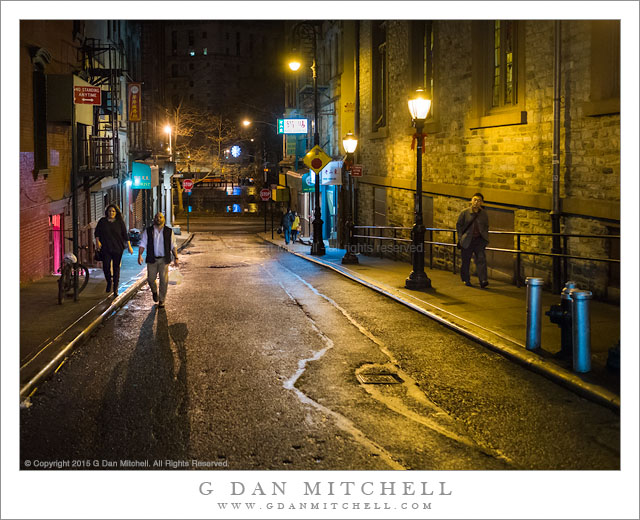

The sensors also have good low light performance, working well at higher ISOs. In fact, these cameras work so well in low light that I “discovered” that I can do handheld night street photography with them! There is noise, as expected, but it can be handled in post.

The sharpness of the images is excellent, likely due to the excellent Fujifilm lenses and the lack on an anti-aliasing filter. I tend to tailor my post-processing sharpening to each camera and lens that I use, and with the Fujifilm files I use slightly smaller radius and a smaller amount of sharpening. (I have to be careful to avoid too much sharpening or lines and edges can show the “jaggies,” especially in very large prints.

If you read online discussions and reviews you will occasionally encounter reports of “smearing” and “plastic” image quality.

- Smearing (or color smearing) is an artifact that can affect colors along sharply demarcated areas of an image, producing a sort of false color in such areas. I have seen it on rare occasions, but only when looking closely at 100% screen magnification, and it seems to me that the problem has decreased over the time I’ve used these cameras. The latter suggests that it is more of a software issue than an inherent issue with the sensor. Out of many thousands of files, all shot in raw mode, I may have seen it no more than a half-dozen times — and in no case was it visible in a print.

- Plastic quality refers to a loss of very fine detail at large magnifications. Because I only see it occasionally, and only in images shot at high ISO to which noise reduction (NR) has been applied, I think that NR is the source. Of course, this can affect files from any digital camera, especially when NR is applied.

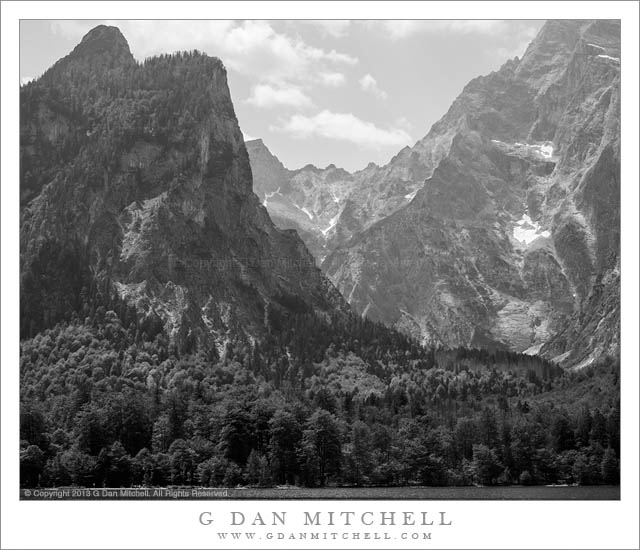

You’ll also read about “Fujifilm colors” online. In general, I tend to feel that brand colors are real but less of a factor than some make them out to be. I also think that they may be partly the result of the different ways that camera and post-processing software interpret image files. For what its worth, I do think that Fujifilm files have a characteristic color response. In the majority of cases I think it is neutral or perhaps good. I especially like what Fujifilm does with my urban and street images and with night photography, and it allows excellent conversions to black and white. I’m less thrilled by what the files do with certain landscape images, especially those with a lot of bright greens or with bluish haze, where I sometimes have to compensate more in post than I might with my Canon files.

There is always the lingering question of whether cropped sensor images are good enough, especially when full frame is an option. A cropped sensor image will not look exactly the same as a full frame image, any more than a full frame image will look exactly the same as a medium format image. All else being equal (though it rarely is!) a larger sensor with more photo sites can produce an image that is better in some ways. But how much better and with what trade-offs? My view is that for the photography I tend to do with this camera, the pluses outweighs the minuses. And, as a bottom line, I can reliably produce wonderful prints at 18″ x 24″ (equivalent to uncropped 18″ x 27″) from my 16MP X-E1 and larger from my 24MP X-Pro2. Unless you regularly print larger than that these cameras produce excellent quality — and if you do print larger you are probably looking at a full frame camera and an overall larger system, and you’ll likely be working from the tripod.

Functionality

The way the camera functions is often quite important. In the rush to compare image quality to the nth degree, some photographers forget this. The size and weight of the gear can be important. The location of controls and the way the camera fits your hand make a difference. Functionality of features such as exposure compensation, autofocus, metering, and more can be critical for some types of photography.

If you like the functionality and interface of your current camera system you will likely have to adapt to some extent when you use the small Fujifilm cameras. I certainly had to. During my first weeks with the system I began to have some doubts — my fingers would sometimes activate settings accidentally, I wasn’t always immediately sure where to go to change a particular setting, and I felt that the small camera was sometimes awkward to hold and operate.

However, because I had good reasons for wanting the smaller and lighter system to work — primarily related to travel photography — and because I have some experience with a variety of interfaces, I stuck with it and thought about how I needed to adopt different ways of operating this camera. (I’m sure the adaptation would have required equivalent changes if I had begun with the smaller Fujifilm camera and then switched to a large DSLR.) Soon I figured out how to hold the camera effectively so that it felt comfortable and I didn’t hit controls by accident, and the menus and other operational controls became second nature. Once that happened I became mostly quite happy with the interface — as much so as I am with my other cameras. In other words, it is overall just fine, but with a few remaining wrinkles. (I still find it too easy to accidentally move the exposure compensation dial, even on the new X-Pro2.)

Fujifilm cameras generally adopt a design approach that dedicates manual control devices to lots of features, making them feel a bit more like classic film cameras. In many other digital cameras today, settings are made via a software interface that may reassign a knob to control a variety of settings. However, as I sit here looking at my X-Pro2 body I see knobs for shutter speed, exposure compensation, and ISO; switches for things like AF mode and (some) lenses with an aperture ring and even old-school depth of field scales. While these are emphatically modern cameras, the design aesthetic makes them feel more like older cameras.

Battery life

Battery life is a weak point for all mirrorless camera systems and Fujifilm is no exception. I consider myself very lucky to get 300 photographs from a battery, and sometimes it is a fair amount less. I tend to carry extra batteries, and on long trips I’ll carry up to four and expect to recharge some batteries daily.

To be fair, this is fairly typical of mirrorless cameras as a breed. (It is also about what I get from my Canon 5DsR when I shoot entirely in live view mode.) Looked at one way, this is disappointing when we compare to DSLRs that regularly get 1000 or more exposures from a battery. On the other hand, the batteries are very small and changing them takes a few seconds.

For some reason, Fujifilm insists on shipping battery chargers that are not only large, but which also have long, heavy power cables. This is odd, given that many other manufacturers provide more compact chargers that plug directly into the wall. Many users will do what I did – purchase a third-party charger that is smaller and does not use the long power cable.

Camera body options

Regarding interface issues, the X-Pro2 (and, by extension, the X-Pro1) deserves a bit more discussion. The X-Pro models use an ingenious hybrid electronic/optical viewfinder system. (My descriptions will be based on the X-Pro2.) The optical viewfinder (OVF) provides an “old school” optical and direct view of the scene — there is no blackout when you press the shutter, no video lag or odd colors, and you can see things outside of the image frame as you compose. It overlays electronic display elements on this “real” image — exposure information, focus point indicator, frame lines, and more. By pressing a lever on the front of the camera you can switch to a full electronic viewfinder (EVF). While this is a video image, with some image quality downsides, it gives precise frame edges with any lens, works in very low light, and does an even better job of superimposing data on top of the scene.

There are some advantages to this “best of both worlds” design. I like the OVF for street photography, though the EVF works better for night photography. The OVF is great for most primes between moderate wide to short telephoto lengths, while the EVF is far better for extreme focal lengths and a much better (or the only!) solution for shooting with zoom lenses. I like it, though it has taken me some time to learn it, and because of the number of options it is more possible to forget how to quickly go from one mode of display to another.

The alternative is the X-T1 or the upcoming X-T2, which are often described as “DSLR style” cameras due to what looks like a pentaprism “hump” on the top of the camera. These cameras have a highly regarded EVF that some think is the best currently available, but no OVF option at all.

Which is better? I don’t think there is a clear answer to that — it is a subjective matter that goes to ones shooting style. I would guess that the majority of photographers will be very happy with the EVF-only X-T models, especially if they are replacing a DSLR and they want to use zoom lenses. Folks who shoot a lot with retro primes (like me!) may prefer the X-Pro models.

An alternative is the current X-E2s (or the X-E2, which is still available as of the time of this writing), a smaller body with the same 16MP sensor that makes no attempt to look like a DSLR. This produces a very small and light camera that might be ideal for those who are really looking for the smallest option. (I’m hopeful that Fujifilm will eventually produce a X-E3 with the same 24MP sensor using in the X-Pro2 and the X-T2.)

Autofocus

When it comes to the autofocus (AF) performance of mirrorless cameras, two questions come up frequently: “How good is it?” and “How good is good enough?”

These are difficult questions to answer in an objective and concrete manner. Mirrorless cameras have a history of providing very slow autofocus, especially in low light and with low contrast subjects. I first used such cameras over a decade ago, and the autofocus was downright lazy, and it was not unusual for the camera to just give up without achieving focus in difficult situations.

Great strides have been made since that time. I’ll use my X-E1 as an example. In most cases it was “fast enough” for the kinds of photography that I did with that camera – but I did not usually do things that stressed AF like sport or wildlife photography. I was able to use the camera effectively for street photography, but I was always aware of the less than immediately AF. I would try to prefocus if I thought a shot was coming. I would AF on some high contrast subject at the same distance as the subject and recompose. And sometimes I missed photographs because the camera did not acquire focus.

The situation is much better with the X-Pro2. AF is considerably faster and in most shooting situations I don’t think about it being slow, especially in decent light and when using better lenses and photographing subjects with detail and contrast. I can still miss an occasional shot due to misfocus, but that can happen even with my DSLR.

Is it as fast as my DSLR? I don’t think so. It is entirely effective for many kinds of photography, and I usually don’t notice it being slower. But I would not take my Fujifilm mirrorless camera to photograph birds in flight or action sports. For such subjects, I still am almost certain to take my DSLR.

So, how to characterize it? I would say that AF performance is good. In most cases it is functionally as effective as using a DSLR. In marginal situations that really challenge an AF system, the DSLR will still likely be better.

The cameras do provide three focus system choices. There is a single shot mode (the one I use most of the time), a continuous focus mode that might be useful for moving subjects, and a manual mode. Selection is by means of a convenient level on the front of the camera that you can operate without taking your eye away from the viewfinder.

Exposure

The Fujifilm cameras provide modes of operation ranging from fully manual through partially automatic (aperture and shutter priority modes). Depending on the model exposure compensation may range up to 5 stops in both directions.

The Fujifilm files — at least the raw files, as those are what I always use – provide a lot of exposure latitude. In typical exposures it is possible to recover detail from very bright highlights in post, and it is also quite possible to push shadow brightness several stops to avoid blocked shadow areas.

Fujifilm lenses

Fujifilm deserves a great deal of credit for the high quality of their lenses, and this has played a large role in the success of the system. When I got my first Fujifilm digital camera I had no idea that the lenses were as good as they turned out to be. I was expecting decent but unremarkable performance, and I distinctly recall my pleased surprise with I post processed the first batch of photographs made using the 35mm f/1.4 lens. These lenses are, in every way*, comparable in quality to the best from Canon and Nikon.

*OK, there are occasional oddities. Take the bizarre lens hood on the otherwise very nice Fujinon 60mm f/2.4 macro. Please. Take it. Really. (We replaced ours with a tiny third-party hood.)

Fujifilm initially released the cameras with a lot of small autofocus prime lenses, such as that 35mm f/1.4. The package of that lens and the X-E1 is very small, and I quickly discovered the advantages of working with small, unobtrusive gear. Early on I was photographing in a crowd at Balboa Park in San Diego. I recall lifting the camera to make some photographs of the crowd and the surroundings, and I was shocked that no one seemed to even notice me. That was most certainly not the case when I used the bigger Canon equipment.

Initially there were not that many lenses available — a basic 18-55mm zoom (though a very good on), a few primes in the 14mm to 35mm range, a 55-200mm zoom, a 60mm macro, and not much else.

However, Fujifilm has moved aggressively to expand their lens offerings, with every one of the lenses providing good quality and reasonable prices. (The prices are even more reasonable when you take advantage of one of the frequent Fujifilm promotions.) Unlike some companies that are secretive about upcoming lenses, Fujifilm shares a lens roadmap that outlines current plans for future releases. (Note that future releases are not cast in stone, and some future lenses have not appeared as products.)

Initially Fujifilm seemed to focus mostly on prime lenses, and virtually all of them were top-notch, from a beautiful little 14mm f/2.8 lens up to the large aperture 56mm f/1.2 and the 90mm f/2. (Since Fujifilm camera use a 1.5x cropped sensor format, multiply these focal lengths by 1.5 to determine full frame angle-of-view equivalents.) Since then the company has filled out their zoom lens offerings, with models that match the functionality of the traditional high-end zooms from the likes of Canon and Nikon and which now cover the range from ultra wide to very long telephotos.

My photography mostly uses the excellent and relatively small Fujifilm primes. Other photographers may well have different preferences that I do, but this is ideal for the way I most often use these cameras. Since I have a different and much larger system for my tripod-based work, I look to the Fujifilm system to provide a much smaller and lighter system, one that is especially suited to handheld photography, and to quick and intuitive work in the street. The small Fujifilm primes are not only optically excellent and small, but they also incorporate effective autofocus. The adds up to a package that is light, small, functionally effective, and optically excellent.

I have used three of their zooms. I have a small amount of experience with the popular (and recommended, for many users!) 18-55mm variable aperture lens. I also use or have used two longer zooms, the 55-200mm variable aperture lens and the 50-140mm f/2.8 lens. The latter lens is not small! However, everything is relative, and it is small by comparison to my functionally equivalent Canon 70-200mm f/2.8 lens, especially when attached to the X-Pro2 rather than my 5DsR!

I have included a list of current Fujifilm lenses at the end of this article.

The bottom line

So, how good are these cameras, and what kinds of photography are they best suited to? Should you replace your DSLR with a Fujifilm mirrorless system? Which model should you get?

These are complicated questions, and the answers are always a bit subjective and personal.

My own approach has been to use the Fujifilm system for portions of my photography, and to use them to augment rather than replace my DSLR system. The shortest answer to questions about how I use the Fujifilm system is “for street and travel photography.” Both of these benefit from smaller and lighter equipment, but both require high quality equipment that can produce excellent image quality. They also require cameras that are flexible and intuitive to use. For me, the Fujifilm cameras have replaced my DSLR system for travel and street photography. I do not remember the last time I used anything else for this kind of photography.

But that’s not all I use them for. I have also used the for a lot of event photography, especially when I want to have a low profile and not distract my subjects. Although I’m a dyed-in-the-wool full frame photographer when it comes to my landscape photography… I’m now contemplating using a two zoom lens Fujifilm setup for a possible long backcountry trip next summer.

Should you replace your DSLR with a Fujifilm mirrorless camera? I do know people who have done exactly that, and there are photographs doing work ranging from landscape photography to weddings who have made that choice. Considering the range of bodies and lenses available today and the fact that image quality can support relatively large prints, this is a viable option for some photographers. For anyone who doesn’t tend to make large prints but who does like smaller and lighter gear, these cameras can easily be all you’ll need.

Other photographers may do what I have done, namely augment their larger systems with the excellent but much smaller Fujifilm system for work where small size is paramount.

As to the which model question, it would be easier to answer if there were any poor cameras among them, but there aren’t. Here’s a quick rundown.

X-100t — This is a pure, fixed lens, rangefinder-style 16MP camera with a 35mm equivalent lens. For quick and close-in photograph (like some street photography) this is a very small and light and quick camera.

X-E2s — This is the smallest of the interchangeable lens Fujifilm cameras. It comes with updated AF and other features and uses the venerable 16MP sensor. It is the least expensive way to try out the Fujifilm mirrorless system, and I successfully used its X-E1 predecessor for three years with very good results.

X-T1 and XT2 — These are DSLR-style mirrorless bodies, know especially for their excellent electronic viewfinders. For photographers planning to use extreme focal lengths and/or zoom lenses, the purely electronic viewfinder has a lot of advantages. The X-T1 has a 16MP sensor and the XT2 has the same 24MP sensor used the X-Pro2. I think that among buyers looking for an upscale option this will be a more popular camera than the X-Pro2.

X-Pro2 — This is a very high quality camera featuring a hybrid OVF/EVF system, optimized for things like street photography and mainly for using interchangeable prime lenses from wide angle to moderately telephoto — lenses that work well with the optical viewfinder. The camera can also work with longer and shorter lenses and with zooms, though you’ll likely revert to the EVF for those purposes.

In the end, Fujifilm has created a very viable camera system including a range of cameras suited to different users, along with an extensive selection of lenses. Many photographers will find the Fujifilm system to provide everything they need, and others will find it very useful to augment their existing system with Fujifilm gear.

Questions? Comments? Please share at the end of this article.

Related articles

- A Small Test: Fujifilm X-Pro2 Mirrorless Camera and Active Subjects

- Fujifilm Announces XT2 Mirrorless Digital Camera

- Why Fujifilm Mirrorless?

- TakingStock of the Fujifilm Mirrorless Cameras

- Sony A7rII versus Fujifilm X-Pro2

Cameras/bundles

-

Mirrorless Digital Cameras

Accessories

- Fujifilm M Mount Adapter for X-Pro1 and X-E1

- Fujifilm HG-XE1 Hand Grip for X-E1 Digital Camera

- Fujifilm XT-2 Vertical Power Booster Grip — B&H | Adorama

- Fujifilm EF-X500 Electronic Flash — B&H | Adorama

Prime Lenses

- XF14mmF2.8 RXF* — B&H | Adorama

- XF16mmF1.4 R WR — B&H | Adorama

- XF18mmF2 R — B&H | Adorama

- XF23mmF1.4 R* — B&H | Adorama

- XF27mmF2.8 — B&H | Adorama

- XF35mmF1.4 R* — B&H | Adorama

- XF35mmF2 R WR* — B&H | Adorama

- XF56mmF1.2 R — B&H | Adorama

- XF56mmF1.2 R APD — B&H | Adorama

- XF60mmF2.4 R Macro — B&H | Adorama

- XF90mmF2 R LM WR — B&H | Adorama

Zoom Lenses

- XF10-24mmF4 R OIS — B&H | Adorama

- XF16-55mmF2.8 R LM WR — B&H | Adorama

- XF18-55mmF2.8-4 R LM OIS — B&H | Adorama

- XF18-135mmF3.5-5.6 R LM OIS WR — B&H | Adorama

- XF50-140mmF2.8 R LM OIS WR* — B&H | Adorama

- XF55-200mmF3.5-4.8 R LM OIS — B&H | Adorama

- XF100-400mmF4.5-5.6 R LM OIS WR — B&H | Adorama

- XC16-50mmF3.5-5.6 OIS II — B&H | Adorama

- XC50-230mmF4.5-6.7 OIS II — B&H | Adorama

Teleconverters (compatible with 50-150mm and 100-400mm lenses only )

If this article helped you make an equipment decision, please consider making your purchase through an affiliate vendor using the links found below. Your price will be the same, but a small fee will be returned to help support this website and my writing.

© Copyright 2016 G Dan Mitchell – all rights reserved.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | LinkedIn | Email

All media © Copyright G Dan Mitchell and others as indicated. Any use requires advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Discover more from G Dan Mitchell Photography

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.