A photographer and friend asked me for my thoughts on mini medium format, or “miniMF,” camera systems. I told her the answer was complex and that I’d write it up at the blog. Here it is!

I have attempted to include several things in the article: a bit of background regarding formats, some objective facts (“the numbers”) about them and their relationships, pluses and minuses of various options, my own current subjective thoughts on what this means to me, and a few alternative perspectives.

The evolution of digital medium format cameras has been among the most interesting photographic developments over the past few years. High MP backs from companies like Phase One and Leaf became the high-end standard for digital image making, and other companies have recently entered the market. The larger sensors may provide improved image quality in several ways: greater system resolution, greater pixel resolution, improved dynamic range, less noise, and more.

It wasn’t that long ago that digital formats larger than full frame were out of reach for nearly all photographers, with costs that were frequently many tens of thousands of dollars, often for only the digital back, which had to be attached to a medium format body.

However, in the last few years several manufacturers have driven down the cost of camera systems using larger-than-full-frame sensors, and now digital “medium format” (more on that term in a moment) bodies are available for less than $7000. A range of manufacturers are now in this market, including Fujifilm, Pentax, and Hasselblad.

When the costs of larger sensor bodies were in the mid-$20k and up (sometimes very up) range, few photographers using full frame DSLR or mirrorless cameras could realistically consider them as options. But the current $6500-$9000 price isn’t that much higher than the most expensive full frame bodies. At these prices the potential improvements in image quality are enough to make folks take a closer look, especially if they are photographers who produce large and high quality prints on a regular basis.

I began to pay attention when the miniMF Pentax 645d came out some years ago (though I was a bit disappointed to find out that the sensor wasn’t really “645” size), and my interest only increased as Pentax updated to the 645z and then as Fujifilm and Hasselblad brought out competing products. I thought a lot about the possible value of such systems for my photography, and I considered getting one. I haven’t done ao — though I won’t rule it out in the future — but I would like to share some of my musings about the choices.

What is “medium format” anyway?

The term medium format, as used to describe film formats, has always been a bit broad, generally referring to roll film formats larger than 35mm film but smaller than large format — which most photographers think of as 4″ x 5″ and larger. More specifically, medium format film was 6 centimeters wide, and various medium formats represented a range of ways of using the area presented by such film. There was not just one medium format standard, and variations include 645 (which might have been more accurately called “4.5×6”), 6×6, 6×7, 6×9, and more. (Note that the actual image size was smaller than the 6cm film width.)

The difference between film with a 6cm width and 35mm film (with its 35mm width yielding a 24mm x 36mm image area) is substantial. The significantly larger film image area produced higher resolution, greater system resolution (a given level of lens quality will produce a sharper print from the larger format), and noticeable differences in depth of field. Prints from medium format film could be quite large, yet the cameras could be smaller and less unwieldy than typical large format equipment.

Digital medium format

A number of manufacturers produced digital medium format backs over the years. The largest of them had an area similar to that of 645 format film, though others were somewhat smaller. Pixel resolution varied, and over time it increased, to the point that 80MP to 100MP backs were produced — and even greater resolution is available today.

These backs provided image quality advantages — enough so to convince some large format film photographers to “move down” to them. However, these backs often had some downsides, too. They did not support very high ISO values, and they were generally not useful for very long exposures since noise became an issue. They were (and are) heavy and bulky. They use battery power quite quickly. Perhaps of greatest significance, they typically were extremely expensive. (One friend referred to his breaktakingly expensive 80MP Phase One back as his “million dollar back!”)

With these factors in play, two things were often regarded to be true about these systems: they could produce extremely high image quality and their cost was far too high for all but a small number of photographers.

Mini Medium Format — “miniMF”

In 2010 — wow, has it really been that long?! — Pentax announced its 645d, a self-contained 39MP “digital medium format” camera, at a price that was well under $10,000. The camera leveraged Pentax DSLR technology, with a more flexible interface than on the separate backs, and with performance that was, in many ways, similar to that of DSLRs. At the time of its announcement 39MP was considered an extremely high sensor resolution, well above what was available in the full frame format. Pentax also had a tradition of producing fine medium format film equipment — and older Pentax MF lenses could be used with the digital camera alongside newer lenses designed for it.

Unfortunately, Pentax chose to identify the camera with the familiar “645” medium format film designation. Some, and I’m among them, regard this as misleading marketing puffery on the part of Pentax. This was not a 645 format digital camera. It used a new sensor format that was/is larger than 24mm x 36mm full frame but significantly smaller than the familiar medium formats based on 6cm wide film, and it most definitely does not use the familiar 645 format. The Pentax sensor had, and still has, 33mm x 44mm dimensions. (In order to differentiate between traditional film “medium formats” and these smaller sensors, I and others refer to them as “miniMF” sensors and cameras.)

A 33mm x 44mm sensor is clearly larger than a 24m x 36mm sensor, and if all else is equal (though it rarely is) it has the potential to produce objectively measurable increases in image quality over full-frame. One way to think of the difference between these sensors is to recognize that one horizontal 33mm x 44mm frame might be, roughly speaking, close to what you get by stitching two vertical 24mm x 36mm full frame images together, allowing for overlap.

(That is quite different as saying miniMF is twice as large as FF, and I’ll have a lot more to say about the comparisons later in this article.)

Today’s miniMF cameras

In the last couple of years we have seen a veritable explosion of mini-MF sensor based options. Some highlights as of the current time include the following.

- Pentax updated from the 645d to the Pentax 645z, with a 51+MP sensor and various other attractive improvements. (When you look at a fully outfitted 645z you may well be reminded of the appearance to traditional MF cameras — it is relatively large and bulky and has a similar shape.) Body price is a few dollars less than $7000.

- Hasselblad introduced the tiny X1D-50c using the same format and a very similar sensor that is also about 50MP. Of the three, this has the most compact body, partly the result of using a mirrorless system rather than the SLR system of the Pentax. Body price is approximately $9000.

- Fujifilm introduced the Fujifilm GFX 50S, using essentially the same 51.4MP sensor founding the Pentax camera, but with less bulk due to the mirrorless design. Body price is about $6500. (Since I originally wrote this article, Fujifilm also introduced the 50R, a smaller, lighter, and less expensive rangefinder-style version of their camera, priced at close to $5000. Update 5/23/19: Fujifilm has now introduced a GFX 100MP model at a price of about $10k. It is also now possible to get the 50MP models for substantially less than the original list prices.)

Compared to a few years ago, those prices look quite attractive. The prices of the 50MP GFX models are downright remarkable, especially for a product called “medium format.” But keep in mind that while the sensor is larger than full frame, it isn’t really what we used to call medium format.

Attractions of miniMF systems

As we know, all else being equal, the system with a larger sensor area has the potential to produce better image quality and other interesting differences.

- In some cases — for example the 39MP 645d when it was announced in 2010 — the larger sensors can have more photo sites (e.g. – “more megapixels”), potentially providing increased image resolution. (The 50MP miniMF cameras have more megapixels than current mirrorless and DSLR offerings from Sony and Nikon, for example.) This is appealing to photographers who are producing very large prints.

- Even when the sensor resolution of a larger and smaller sensor system is essentially the same — for example when comparing the Canon 5DsR to the 50MP miniMF cameras — the larger sensor still may be able to produce higher system resolution. Basically, if a lens has a given level of resolving ability, often measured in line pairs per millimeter, a sensor with “more millimeters” of width may be able to resolve a greater number of line pairs across the image.

- When a given number of photo sites is distributed across a larger sensor area, the individual photo sites can be larger. This may potentially produce increased dynamic range, better low light performance, and lower noise if all else is equal.

- Some former medium format film photographers are attracted to the potential to adapt their existing collections of MF lenses to the newer cameras.

- There are differences in the depth of field (DOF) performance of lenses on larger sensors. A given aperture will produce narrower DOF on a larger sensor, and smaller apertures may be used before diffraction blur becomes an issue. For example, a miniMF camera at f/2.8 might produce about the same DOF as a full frame camera at between roughly f/2 and f/2.5. (The exact relationship depends on what aspect ratio you use with either format. One limitation on this advantage is the fact that lens with large apertures are more readily available for full frame cameras — e.g f/1.4 and larger apertures on full frame primes versus f/2.8 apertures on miniMF primes in many cases.

So, since these things are all better, that should seal the deal, right?

Maybe and maybe not. There are several other factors to consider. There are some downsides to the larger sensor systems, too, and each photographer needs to determine whether the upsides or downsides are more significant in their work. In addition, there are reasons to both accept the potential for image quality improvement and recognize that the improvement may not result in visibly better photographs.

Downsides of miniMF systems

Here is a short list of issues to seriously consider if you are looking at miniMF camera systems.

- While the cost is lower than it once was, it is still higher than high-end DSLR and mirrorless cameras with similar pixel resolution. For example, the cost of my Canon 5DsR body is about half that of the least expensive miniMF systems.

- New lenses for miniMF systems are often rather expensive. (Some older MF lenses can be considerably less expensive, though not all will take advantage of camera automation features and some may require adapters.)

- There are bulk and weight issues. For example, the Pentax 645z body is larger than typical DSLR and mirrorless full frame bodies. (The Hasselblad and Fujifilm mirrorless bodies reduce the size advantage of full frame DSLRs, though mirrorless full frame bodies are still much smaller than mirrorless miniMF bodies.)

- In all cases, lenses that provide equivalent angle-of-view coverage must, by definition, be longer. For example. the Fujifilm 63mm lens is angle-of-view equivalent to a 50mm lens on full frame. If you work in the studio this probably isn’t much of a concern. If you carry large amounts of equipment on your back into the wilderness or do street photography, it may be.

- The miniMF equivalents of full frame large aperture lenses (e.g. – 50mm f/1.4 and larger) are unavailable or nearly so on miniMF systems. (Some full frame lenses may be usable on miniMF with adapters, especially if you are willing to accept images compromised by vignetting.)

- The range of available lenses is limited on miniMF by comparison to full frame. For example, I rely on four Canon L zooms in my landscape photography: 16-35mm, 24-70mm, 70-200mm, and 100-400mm. An equivalent set of miniMF lenses is not available, so I would have to eschew certain types of photography with such a system.

- The miniMF cameras generally operate a bit more slowly than full frame cameras. For example, it may not be possible to even get 2 frames per second out of them.

More complex comparisons

If you thought that the preceding two categories — essentially the pluses and the minuses of miniMF — are enough to come to a conclusion, things are about to get a bit more complicated. There are two categories of issues. One is very subjective — how well does your photography adapt to miniMF? The second is a bit less subjective, but still a bit tricky to figure out — where there are differences, how large are they, and will you see them?

I alluded to the first area of concern earlier when I pointed out that I like to use a range of zoom lenses for my landscape photography — and that equivalent lenses are not available on miniMF at this point. For me, this is a significant issue — it would mean that I would not be able to make certain types of photographs that I currently can make with my FF system. Another photographer might feel quite different about this — for example if she or he prefers to photograph with a few prime lenses for which equivalents are available for miniMF, or is happy to use lenses in a fully manual mode. Something that is a deal-breaker for one photographer may not even be an issue for another.

Each photographer needs to take a cold, hard look at this before jumping to miniMF. (Some time ago I had a conversation with a colleague who has long used digital MF systems and now uses the 645z. I mentioned to him that I was becoming interested in MF, and he replied by pointing out that my use of long focal lengths would be problematic, and that I might be better off with FF.)

The second issue — the magnitude of the difference issue — is big enough that I think it warrants its own section.

How much of a difference is there?

Despite my serious interest in the miniMF systems, so far my answer to that question is, “there is a difference, but perhaps not enough to affect my photographs in a big way,” along with “not enough to override other practical downsides.” I may change my mind at some point — I can even think of some things that might convince me — but certain factors have dampened my enthusiasm for now, even though I was ready to move in that direction.

Keeping in mind that fact that the larger sensors are able to produce higher resolution, lower noise, better performance from a given lens, and differences in depth of field performance, let’s look a bit closer. I’ll start with an attempt to better understand just how much of a difference there is between the full frame and miniMF sensor formats. (The simple answer up front is “probably less than you think.”) Let me begin with a chart.

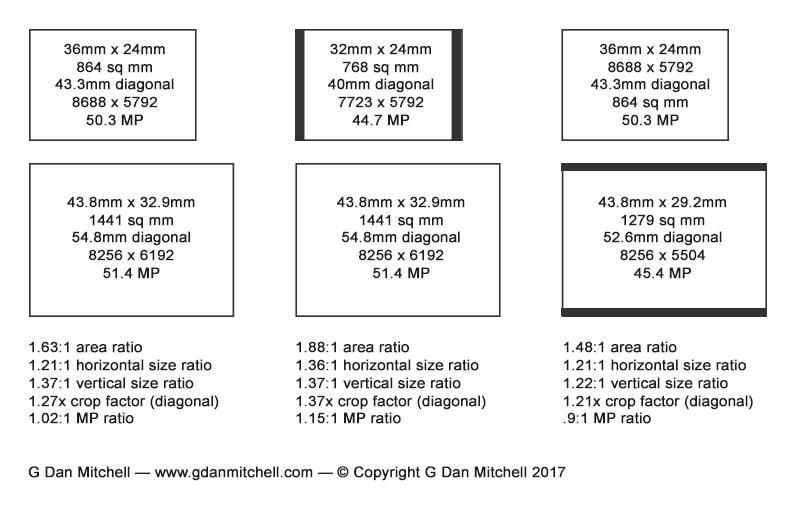

The chart offers some important comparisons between the 24mm x 36mm full frame format and the 33mm x 44mm miniMF format, and I believe it helps photographers who are trying to get a handle on this comparison.

The images graphically represent the relative sizes of the sensors. The black areas represent portions of the image that you would not use if, respectively, you used a full frame camera to shoot the 4:3 aspect ratio (as I do), or if you used the 3:2 aspect ratio on miniMF. Perhaps the two most important and logical data points are the megapixel dimension comparisons and the crop factors, which are a way to represent the relative sizes of the sensors in a photographically meaningful way.

There are three columns, each showing a pair of images and some additional data about the comparisons.

- The first column is meaningful to photographers who would switch from the 3:2 aspect ratio on their full frame cameras and start using a 4:3 ratio for their photographs made on miniMF. Here both systems provide approximately the same number of megapixels and the crop factor is 1.27x.

- The second column is meaningful to photographers who currently use the 3:2 ratio full frame format to produce 4:3 aspect ratio prints — they are currently losing about 1/9 of the pixels and frame width on their full frame systems. Here the miniMF system provides more than 7 additional megapixels than full frame, and the crop factor is1.37x.

- The third column is meaningful to photographers who prefer the 3:2 aspect ratio of their full frame systems and who would plan to continue to use that ratio with the miniMF system — they will lose pixels from the miniMF sensor. Here the miniMF system ends up with about 5 fewer megapixels than full frame and the crop factor is only 1.21x.

Let’s consider those crop factors for a moment. The crop factor is a way of quantifying the relative difference in sensor size that is photographically useful when comparing one sensor to another of a different size. (It is often used to calculate what focal lengths will yield the same angles-of-view with different sizes of sensor.) You may be familiar with so-called cropped sensor cameras. The two most common are the 1.5x and 1.6x crop factors. Without getting into too many details of what crop factor is, let’s simply note the size of the factors here, 1.5x and 1.6x.

There are a lot of discussions and arguments about the significance of crop factor differences. Most people will agree with the idea that in very small photographs, such as most screen-displayed images, the difference in image quality between the 1.5 or 1.6 crops and full frame is not significant in terms of resolution. (There are some depth of field effects that may be visible if you compare carefully.) However, as reproduction size increases, most anyone will agree that the image from the smaller sensor “breaks down” sooner, and that the image from the larger sensor, all else being equal, holds up at larger print sizes. Regardless, many photographers have some sense of how to think about the differences between the cropped-sensor formats and full-frame format.

(For my part, I’m confident in 20″ x 30″ prints from my 24MP 1.5x cropped sensor system, and I may be able to go a bit larger with some images. I’m confident about going considerably larger with my 51MP full frame system — 30″ x 45″ looks very good and, here too, larger than that is sometimes possible.)

Let’s use crop factors to compare full frame to miniMF, and consider how the relative differences between them compare to the differences between 1.5x/1/6x crop and full frame. (See the earlier chart for more details about the full-frame and miniMF values.)

In the case most favorable to miniMF, where the crop factor of miniMF is said to be 1.37x, it is worth noting that the difference is smaller than that between full frame and traditional cropped factor formats. In the case least favorable to miniMF, the crop factor is barely more than 1.2, an even smaller difference.

Given the same MP count from both sensors (and here the crop factor is about 1.27x), any resolution advantage would be attributable to two potential sources.

- The larger sensor system could produce greater system resolution. For example, if a lens was unable to resolve at the level of the 50MP sensor on the full frame camera but was able to on the 50MP miniMF system, the latter’s overall image resolution might be a very small amount better. (However, the best lenses can resolve the detail available on the sensor with full frame systems, so there might literally be no visible difference.)

- The larger sensor system will produce slightly smaller depth of field at a given aperture — between about 1/2 and 1 stop, depending on the preferred aspect ratios. It also allows the photographer to use a slightly smaller aperture (and increase DOF) with the same amount of diffraction blur. In side-by-side tests with very large aperture full frame and cropped sensor systems, where images have been chosen to make the differences visible, there are subtle but visible differences. But note two things. First, the difference between full frame and miniMF will be smaller than that between FF and cropped sensor. And lenses with the very large apertures found on full frame (f/1.4 and f/1.2) are generally unavailable on full frame systems — meaning that the miniMF systems and lenses are often less able to narrow depth of field by means of extra large apertures. (It is possible to adapt a few full frame large aperture lenses to miniMF systems — though with loss of AF and AE features, and in some cases the corners of the image — and achieve very small DOF.)

(The larger sensor could also produce non-resolution advantages, such as greater dynamic range and lower noise levels.)

I need to test this, and I have had preliminary discussions with a friend who uses the Pentax 645z system about doing some controlled comparison between his camera and my 5DsR. Until then, logically we can say that a) there are differences, but b) the differences will be smaller than those between full-frame and cropped sensor formats. (Depending upon how one compares the full-frame and miniMF results — see earlier chart — the DOF difference is between about .5 and 1 stop. For example, in the case most favorable to miniMF — using a 4:3 ratio on both systems — to replicate the DOF from a f/2.8 lens on miniMF one would use approximately f/2 on full-frame. In the case least favorable to miniMF — a 3:2 ratio on both systems — one would use f/2.5 on the full-frame camera.)

What about dynamic range and noise?

Again, logic tells us that both of these parameters will be better on the miniMF system, and there is plenty of evidence that this is true.

- If we compare my approximately 50MP Canon 5DsR full frame system to the Fujifilm and Pentax miniMF cameras and their excellent Sony-made sensors, it is known that Sony sensors currently have the largest dynamic range.

- The Sony sensors also are known for very clean, low noise images at typical ISO values, and for working quite well in low light.

- The difference in sensor size here favors the larger sensor since the individual photo sites can be larger, therefore collecting more light.

It is impossible to argue that the mini MF sensors are not going to be better than the full frame sensors. But let’s put that in context — and recognize that there is some subjectivity when it comes to understanding the significance of the differences.

If we are comparing a substandard system to one that rectifies image-impairing inadequacies, most serious photographers, all else being equal, will likely adopt the better system. But that isn’t the comparison here. Current full frame digital camera systems from a range of manufacturers are capable of producing excellent image quality. Photographers using full frame systems from manufacturers such as Sony, Nikon, and Canon can reliably produce technically and aesthetically high quality prints at 30″ x 45″ sizes and larger.

So a serious question becomes, “Will I see any differences in my prints that can be attributed to the objective and measurable improvements in dynamic range and noise?” These might include the ability to reclaim detail from very dark areas of a wide dynamic range image, or detectably lower noise.

My thinking on the former issue is that one might, in some marginal cases, find enough difference between the two systems to reclaim a bit more noticeable shadow detail. This won’t be a night and day thing, but rather a somewhat better result in a few cases. In most cases, both systems will do a fine job of capturing the entire dynamic range. (In a number of other cases neither system will have enough dynamic range.)

My thinking on the second issue (noise) is a bit more involved. First, in most of the kinds of photographs for which one might typically consider using a miniMF camera, frankly, noise isn’t really an issue. It was a number of years ago, but today’s full frame systems typically have very low noise. Secondly, again, any difference would be one of degree — not night and day — so in a case of visible noise, the noise might be a tiny bit less visible in the miniMF image.

What is the right choice?

Honestly, I don’t know for sure, and I continue to look at these things carefully. I started out being very enthusiastic about the miniMF systems, especially when I saw that their prices were bringing them within reach. I have long envied friends who were working with digital MF, and I felt that at least some of my work could benefit from the larger format. I was interested enough that I took a very close look at the Fujifilm and Pentax systems, and was primed to buy.

But the more I looked at the comparisons dispassionately, the less compelling I found the miniMF systems to be for my work. They are measurably “better” in technical terms, but the amount of “better-ness” appears to be less significant that, say, between 35mm film and 6×7 film medium format or between digital cropped sensor and full-frame formats. I am not yet convinced that moving to miniMF would typically produce a visible quality improvement in my prints.

And there are other costs. Financial costs are not insignificant. Even with the newly-lower prices of the camera bodies, the lenses are not inexpensive. (Using vintage manual focus MF lenses can reduce the cost.) Some of the lenses that I rely on are unavailable for these cameras. The weight and bulk of the overall camera package is larger, and would weigh more heavily on my back on the trail.

Am I going to get one? Not right now. In the future? I cannot rule it out — if costs continue to come down, more lenses become available, and the sensor resolution increases to a point that I cannot equal with a full frame system.

Is my choice the right one for other photographers? Not necessarily. (See more below.)

But for now, I suppose I could summarize my current thinking as:

- miniMF cameras from Pentax, Fujifilm, and Hasselblad can produce excellent image quality.

- Compared to historic pricing for digital systems with larger-than-full-frame sensors, the prices of these cameras are remarkable.

- These newest models have largely overcome some of the drawbacks of earlier digital medium format options.

- I’m not yet convinced the potential improvement over the image quality of high resolution full frame cameras is large enough to make a significant enough difference in my photographs.

- The upsides of miniMF cameras are not sufficient for me to compensate for the functional downsides of the cameras in my photography (particularly regarding lens availability).

That’s for now. Things can change. We’ll see how I feel in a year or two. (And you may come to a different conclusion.)

One more thing

After writing the initial article, I had a concern that it would be possible to confuse my personal assessment (in the context of my photograph) with application to other photographers. With that in mind, I have added this section to provide some balance, and here is a list of some alternatives to my current personal decision regarding the place of miniMF systems in my work.

- Photographers coming from large format or medium format film may recognize the high quality available from miniMF and be attracted by the smaller size and weight, the ability to work in low light, the more modern operational interfaces, and the excellent image quality. I know of several people who have done exactly this. One moved, over a period of years, from LF film to Phase One backs to the 645z, testing carefully along the way. (I also know other former LF photographers who decided to go straight to full frame digital mirrorless or DSLR cameras, without stopping at digital MF in between.)

- Photographers (like me!) relying on the small Fujifilm x-trans cameras who want to expand to a higher resolution system might forego full frame and go straight to the GFX for their second system, with the idea being that the difference between these two systems might be larger than that between the x-trans cameras and full frame systems from other manufacturers.

- Some folks with plenty of money, hobbyists in some but not all cases, may be interested in these cameras simply to try them out and better understand them. (Or for “bragging rights,” but let’s not go there… Oh, wait, I did! ;-)

- Photographers with an existing collection of certain medium format lenses may find it attractive to keep the lenses and work with a smaller camera body. At the moment this may be most likely to appeal to buyers of the Pentax 645z. (Update: I recently had a chance to use a GFX with adapters allowing the use of the Pentax lenses on the Fujifilm system.)

- A photographer who finds that all of the lenses they prefer are available — and perhaps they already own them — may be more attracted to these systems.

What do you think? Questions? Reactions? Are you considering one of these systems? Do you already have one? Please leave a comment or question below and we’ll discuss!

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | LinkedIn | Email

All media © Copyright G Dan Mitchell and others as indicated. Any use requires advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Discover more from G Dan Mitchell Photography

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Beautiful and thoughtful article Dan. I loved your writing. Currently I use Canon 60D and 200L for Astrophotography. I plan to upgrade my system for two reasons: Higher resolution and Lesser noise. I need to use only one fixed lens between 150 and 250 mm on my motorized tripod. I am still thinking between FF and MiniMF. Which to go for?

In brief, I have not used both and so just reading and imagining!

Your thoughts will be helpful.

Thank you

Parag Mahajani (India)

Hello and thanks for stopping by to read the article and leave a comment.

Certainly the larger sensor system will have the potential to reduce noise and increase system resolution. However, I wonder if you are going to be happy with the lens options. Your 200mm lens on the 60D is the angle-of-view equivalent to a 320mm lens on a full frame system and, depending on how you account for the difference in aspect ratio, perhaps equivalent to about a 400mm+ lens on the miniMF Fujifilm system. Finding the miniMF focal lengths that give you the small angle-of-view coverage that you are used to with your current system is going to be a serious challenge. Right now the longest focal length that Fujifilm makes is 250mm, and this comes with a much smaller maximum aperture. There are some longer non-Fujifilm options that you could probably adapt, but they will be aperture-constrained in the same way, and they will be very big, very heavy, and very expensive!

My first impression is that miniMF may not be all that well suited for what you have in mind. Perhaps a full frame system would get you a bit more system resolution and improve the light gathering and noise characteristics enough. And there are some large aperture primes that give you fairly large apertures, such as the Canon 300mm f/2.8L lens.

On the other hand, if you are thinking of finding some way to use an actual telescope and capture its images on the miniMF system (something that I know little about, I’m afraid!) you could consider the larger system.

Dan

Dan

Good write up and I fall in line with the comments of Jeff. The Pentax is a big block of more weight to carry but the lenses are there, not expensive and they are not focus by wire. Regarding focus by wire; I did not like the look or feel of manual focus with the Fuji GFX. If the Fuji had manual focus lenses that could rack back and forth in and out of focus I would buy the outfit. Especially given the 32-64 zoom. For me a perfect focal length zoom.

Another factor that kept me from plunging into MF is the possibility (bound to happen) of a 100 mp Sony sensor or something close landing in a new Sony or other camera. Sony would be the most likely.

In many ways I pine for the days of 4×5. The lenses were superb, the unit compact and rugged, and a single good exposure was easily printed to 40×50. I don’t regret scanning, changing film, the dark cloth flapping, or $5.00 out with each shutter click.

Claude

Nice write-up Dan. I have been watching the space for quite awhile and like you I remain interested but uncommitted to this “next step” primarily because of the lack of lenses I use on a regular basis on my 135 system. Of the current options I feel like Fuji is the closest body and feature wise but Pentax has the lenses I need, with a body that is too bulky and heavy. Clearly there is more room for lens adaptation on the Fuji and I’ll likely rent a body and some lenses and do some tests…when I can block out some time.

Thanks, Jeff. Sounds like you and I are in about the same place. I agree that the Pentax system currently seems to provide the widest range of lens options, especially when you look at the older Pentax film MF lenses and the newer lenses released since the 645d came out. I actually have one of those lenses — the 80-160 — that I use on my Canon with the Mirex adapter.

The Fujifilm body appeals to me for several reasons. First, I’m already and enthusiastic user of their small x-trans cameras. Second, for a landscape photographer — who carries too much stuff into the field on his/her back! — the smaller and lighter mirrorless body is attractive. (I have some concerns about battery life.) But at this point Fujifilm’s lens options are far too limiting for me. The lenses they have released are appealing, but there must be more before I go there.

I’m less interested in the Hasselblad unit. It is an impressively compact camera, described by some as being “jewel-like.” However, from what I have read, Hasselblad is not very interested in providing the sorts of lenses that I would use on such a camera, namely a range of excellent zooms.

Dan