This is the first of what will be a series of articles looking at steps you can take to improve your chances of producing compelling photographs.

A recent stay in Yosemite Valley during my Yosemite Renaissance artist-in-residency reminded me again that while many aspects of photography are out of our control, there are things we can do to increase the odds of success.

On this visit I had three late April spring days to photograph in the park, which mostly means “in Yosemite Valley” at this time of year when the high country is still snowed in. By non-photography standards, the Valley was beautiful — if a bit crowded. The sun was out, the sky was blue, temperatures were comfortable, rivers were full of early snowmelt, the waterfalls were flowing, there were hints of green in the seasonal vegetation, and too many tourists were already showing up!

I did the usual things: I got up before dawn to find the early light. I stuck around until the last light faded. I returned to subjects that I knew from past experiences to be promising. I considered where the light would be at different times of day. I went looking for new subjects in likely places. I wandered. I kept my equipment with me at all times. I made photographs, and some of them are even pretty good, but at times it was hard to “see” something special in these conditions.

What’s not to like, right? From a photographer’s point of view these are not ideal conditions for photography. As pleasant as nice weather is for hiking and camping and picnicking, it can be hard to find exceptional photographs in such everyday light. I and many of my fellow Sierra photographers prefer interesting and unusual conditions — precipitation, broken light, mist and clouds, some haze.

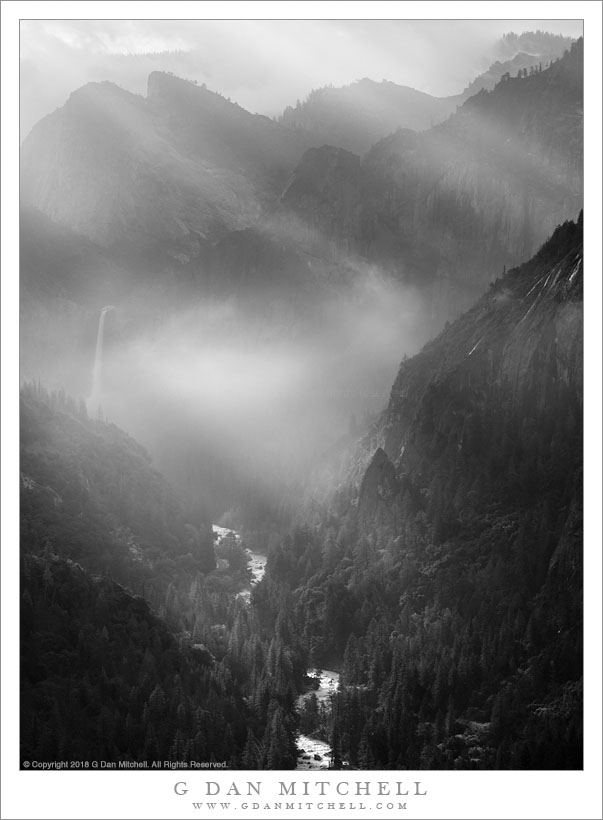

On the final morning I was up and heading into the Valley well before sunrise. The light was unspectacular, with thick overcast cutting off the morning light. But then I caught sight a bit more light in the east, and soon I saw some breaks in the clouds. Within fifteen minutes the conditions opened up and I was treated to an exceptional spectacle of light and clouds and landscape that lasted for several hours, during which I photographed continuously. I made more interesting photographs during these few hours than during the rest of the visit.

To state the obvious, “exceptional” and “unusual” conditions are not the norm. The blue-sky “blah” light is. If you show up on ten randomly selected days, nine of them are going to be, literally, unexceptional, and if you are looking for something unusual and beyond-the-norm you aren’t likely to find it.

The basic lesson is simple: The more you are out there the more likely you’ll be out there for something great.

(This is not to say that you cannot make fine photographs on a non-exceptional day — more on that subject in a related future article.)

Regardless of your situation — and admittedly not everyone can be “there” all the time — you can increase the odds that you’ll be there when exceptional conditions arise.

- Be “out there” as often as you can. A few days ago I watched a Sixty Minutes story on nature photographer Thomas Mangelsen. (What a pleasure to see a story on such a topic on this program!) In one exchange with Anderson Cooper, Mangelsen describes going to a particular location every day for 42 days straight in order to get a particular photograph. Even allowing for potential embellishment of this story (we’ve all been known to “go there”), this story is instructive — and impressive. If you went out to this location once, you would have about a 2.5% chance of encountering what he found on his 42nd day – and a 97.5% chance of missing it! Go ten times and you have a 25% chance of seeing it. It sounds obvious, but the more you are “there,” the more likely you’ll experience a range of conditions including the spectacular.

- Go when conditions look like they may be great. If you are attuned to the conditions and patterns of your subject, make an extra effort to “be there” when good conditions are more likely. Is a weather front passing through? Light may come through breaking clouds as the front departs. Is fog in the forecast? You may find mysterious atmosphere and light. Go on the normal days, but especially go on the special days.

- Go even when the conditions don’t look special. This contradicts the previous point, but if you can only go when things don’t appear to be special, you may be there when a surprise occurs. (Re-read my story of the blah, overcast light I woke up to on the last day of my Yosemite visit.)

- Go even (especially!) when conditions look uncomfortable. The most interesting photographic opportunities often appear when the conditions are challenging. Taking advantage of them may require you to work in rain, snow, wind, heat, cold, darkness… and most certainly to get out of bed hours before you want to. (One of my all-time favorite Death Valley photographs was made on what started as an overcast morning, with gale force winds that threatened to knock over my tripod… but which soon broke up the clouds and sent cloud shadows across a playa as lenticular clouds formed overhead.)

- Accept disappointing days as part of the process. I try to think of an unproductive day as a down-payment on a future great day. They come with the territory. It is impossible to predict with certainty when the best opportunities will arise. Exceptional days are, literally, exceptions, and you’ll experience many normal days in order to be there for that special one. Knowing this, accept the less-than-stellar days as part of the bargain. (Go and photograph anyway, for reasons that I may write about in a future article.)

- Work with the conditions you are given. Even on a day when the light and atmosphere are not what you were expecting, keep your eyes open and perhaps look in different directions, and you may still find something special. And remember that conditions can change quickly and unexpectedly. (I once watched an utterly brilliant sunset appear behind a fading scrim of clouds that had presented a boring scene moments before.)

This is not a comprehensive list of factors. Knowing your subject is important, being able to make predictions of conditions is useful, knowing your equipment helps, along with many other things — some of which I’ll touch on later.

Photography isn’t always fun, easy, or comfortable. Sometimes the photographs don’t come easily. At times conditions can be challenging. It may be cold or wet. You may spend a day not finding what you are looking for. You will wish you could sleep in for another three hours.

But when you persevere and find something special, you will understand why it is all worth it.

Questions? Additional thoughts? Leave a message below…

See top of this page for Articles, Sales and Licensing, my Sierra Nevada Fall Color book, Contact Information and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist. His book, “California’s Fall Color: A Photographer’s Guide to Autumn in the Sierra” is available from Heyday Books and Amazon.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Email

All media © Copyright G Dan Mitchell and others as indicated. Any use requires advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Somewhat long lens, but nothing unusual.

Conditions? Yes!

Great article. Thanks for sharing. Friends and I have been debating where you stood to take this picture for over a week now and we’re no closer to figuring it out. Prepared to share?

Glad you enjoyed the article!

The location is a pretty easy one to find. Rather than taking all of the fun out of it, I’ll give you a hint. It is a well-known (iconic, even) viewpoint that you cannot miss if you come into the park via highway 120 and Big Oak Flat road.

(I think the photograph is more about the conditions that day than about the location itself.)

Dan

hmmmm, that is how I enter the park… I think conditions and maybe a massive lens. Thanks again.