I recently saw – and replied to – a question posted in a photography forum regarding tripods and shooting in high winds. The poster wrote something very similar to the following:

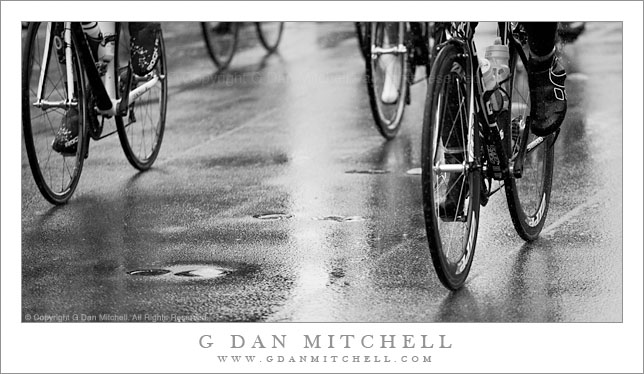

I realized that many shots from a recent trip are blurry because of wind shaking the tripod. Even hanging 10lb weight did not help. So now, I am looking for a new tripod that won’t be affected by wind.

What the writer has discovered is that no tripod is immune to strong winds, especially if you make long exposures and/or use long focal length lenses. Even if you had an absolutely rock-solid tripod, in a 40 mph wind your camera and lens will vibrate enough to create a slightly less sharp image.

So, what to do? You could get the heaviest tripod you can find and weight it down with bags of rocks and what not. But then you are stuck hauling around the dead weight of this tripod the other 95% of the time when you don’t need it. Yes, get a good solid tripod and a good head with good camera brackets, but other things can help in high winds and, in fact, may be necessary even with the best tripod:

- Use a shorter focal length if possible.

- Use a higher shutter speed, even at the expense of a higher ISO, larger aperture, and accept the slightly increased noise or slight loss of DOF.

- Consider using image-stabilization (IS) even with the camera on the tripod in extreme conditions.

- Don’t extend the tripod legs all the way – if possible shoot from down low to the ground with the legs retracted.

- try to brace the tripod against something – rocks, your legs, anything that will dampen vibrations a bit.

- Try to use natural wind screens when you set up – sometimes being in the lee of a wall or tree or rock can diminish the wind enough to make a difference.

- Time your shots for moments of less wind.

- If your exposure times are not extremely long, gently resting a hand on the lens or camera body can dampen the wind-caused vibrations.

- Rather than relying on a single exposure, make many redundant exposures – some will likely be less affected by the wind than others.

- If you have a strap attached to your camera, take steps to make sure it doesn’t flap. Wrapping it around the tripod may be sufficient.

- If conditions permit, consider removing your lens hood.

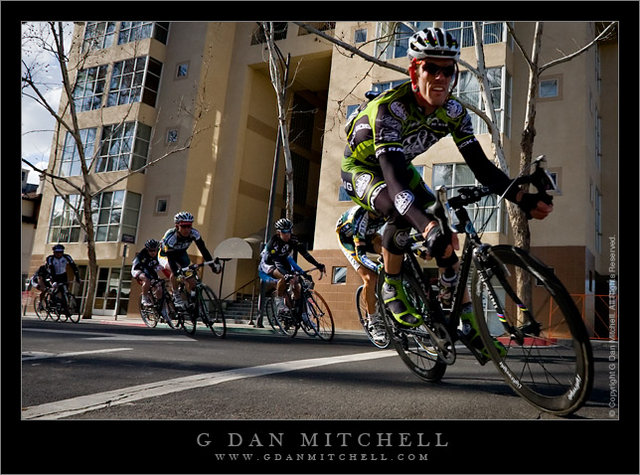

I recall once shooting on top of a bluff at the far reaches of Point Reyes, normally a very windy place and on this day windy enough to almost be scary. But the light was beautiful and I wanted to make photographs from the edge of the bluff. I ended up retracting the tripod legs so that the camera would be lower to the ground, sitting with the tripod braced between my legs, using IS, leaving a hand on the camera to dampen vibrations, raising the shutter speed, and making many exposures. In the end, a good percentage of the images were adversely affected by the wind… but among them were some good ones that were sharp.

G Dan Mitchell Photography | Twitter | Friendfeed | Facebook | Facebook Fan Page | Email