1. Use a camera. The most important and basic tool of the landscape photographer is the camera. Using a camera greatly simplifies the process of capturing photographic images, and without one you’ll likely feel a bit lost. You may have noticed that pretty much all great landscape photographers use a camera – some use more than one! – so take a cue from the pros and make sure you have a camera, too!

2. Get a lens. Having a lens makes your camera much more useful. While a camera is critical to your work as a landscape photographer, without a lens the usefulness of the camera is greatly diminished. For this reason, virtually all successful landscape photographers end up, sooner or later, getting a lens to use with their camera. You’ll definitely want one, too – just like the pros! (Some cameras come with a lens built in – what a useful idea!)

3. Remove your lens cap. How many photographers can tell stories of forgetting to remove the lens cap before making a photograph, only to discover that the results were not what they had hoped for? But you don’t have to learn the hard way! Practice removing your lens cap at home – that way, when you are in the field you will have developed “photographer’s instincts” that will ensure that you remove the lens cap. (The good news is that with digital cameras you don’t have to worry about whether you loaded the film – but don’t forget your memory card!)

4. Photograph interesting things. Although it isn’t universally true, you will probably get more interesting photographs if you photograph interesting things. There are many things in the world, and not all of them are interesting. Look for the interesting things and photograph them. Look around – it is an interesting thing to do! Interesting, yes?

5. Pick the right brand. There are many brands of photographic equipment out there – cameras, lenses, filters, bags, you name it. Picking the wrong brand may hamper your photography; pick the right brand and you may not hamper your photography so much. So be sure to pick the right brand. If you aren’t sure which brand is best, talk to photographers – any one of them can tell you which is best… and why!

6. Light is important. Without light it would be pretty much impossible to make photographs, at least the typical landscape photographs. So if you plan to make typical photographs, look for scenes that are illuminated by… light! Light is your friend. Seek out light and when you see it make photographs. Think about it… how many of the photographers you admire work without light? So, do what the pros do – use light!

7. Pick the right subject. Pick the wrong subject and your photograph won’t be what you wanted it to be, so be sure to photograph the right subject. Seek it out and when you see the right subject make a photograph. Perhaps make several. There are so many subjects in the world that finding the right one can be a challenge, so be sure to apply yourself carefully to this task.

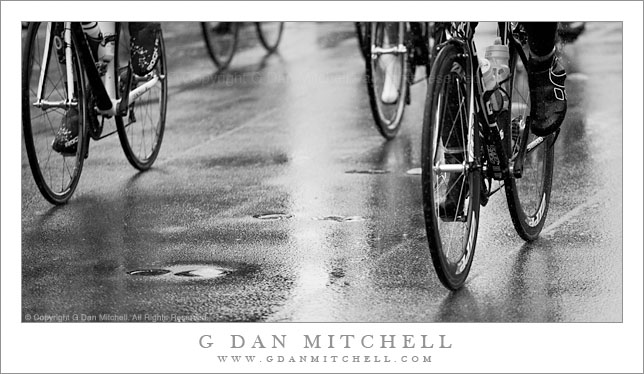

8. Colors are important. Unless you are making black and white photographs – in which case the only important colors are black and white. You’ll want to pay careful attention to color. The most important advice is to focus on color in your color photographs – just like the pros!

9. Focus on what is most important. Some people think that mastering technical issues is the most important thing. Others think that having the right equipment is critical. Some claim that the artistic quality of the photograph is important. (Don’t forget – color is important, too!) Before you make great photographs you’ll have to decide which is the most important in your work. Don’t waste your time being a generalist and trying to do everything – pick one and focus on it! Successful photographers develop a speciality and stick to it. And don’t forget the rule of thirds!

10. Find good locations. There are many popular spots to make photographs, and you can make photographs just like the pros if you seek out these locations and shoot there, too. You’ll have to be attentive, since these spots are easy to miss if you are talking on your cell phone as you drive past them. Some telltale hints include parking lots full of cars and lines of people with tripods. Stop and make a photograph – there is always room for one more tripod! You can probably make one that looks just like those that the other photographers are making! (Hint: You can also visit online photography sites ahead of time – both to find the locations and to save yourself from spending too much time searching for compositions when you actually get there. Your time is precious!)

Good luck!

(I probably should have saved this for April 1, but I couldn’t wait… :-)

For those whose first experience with my blog is this tongue-in-cheek post, I write serious stuff, too, and a related recent post might interest you: Photographic Myths and Platitudes – ‘Landscape Photography Lenses’ (Part I)

Like this:

Like Loading...