An article that I saw this evening at the SFGate website (“Arm’s length: Does filming hold reality at bay?“) got me thinking again about the strange ways that the ubiquitous camera has affected our relationship to the world around us. From the article:

We can film anything today, from anywhere, by simply extending our arm and aiming a device at the subject of interest. Then, almost as quickly, we can beam those images to the world. But is this progress? Are we starting to experience things through miniature screens rather than actually living them by being there? We are taking pictures, but we are distancing ourselves even further from the things we are taking pictures of?

The article opens by describing a group of people waiting for the passage of the peloton in the Olympic bicycle road race who, as soon as the cyclists appeared, raised cameras and rather than experiencing the actual event of the race, looked at in on the LCD panels of the cameras held in front of them, hoping, I presume, to get around to actually seeing race later on their computer screens.

I saw a similar scene unfold – actually I saw a lot of them unfold – recently on a summer afternoon in San Francisco. I had wandered over to the Palace of Fine Arts to, yes, make some photographs of the architecture, the surrounding grounds, and perhaps the people who were there on this sunny day. The Palace is an imposing, classical edifice left over from a worlds fair many decades ago, and it features giant fluted columns and a central structure with a very large and very tall dome. I could write an entire post about the sorts of things that people were doing there related to photography, but I’ll just mention one. When I photograph such a place I actually spend a lot more time just walking around and looking than I do making photographs. I might walk and look for ten or fifteen minutes, spot something, make a few photographs, and then go back to looking. As I walked along the pathway around the lake that sits in front of the Palace, I noticed people feeding the geese and other birds that congregate there. A large group of “kids” (perhaps high school age?) who appeared to be on a group visit from another country came by just as a small group of geese swam past. They rushed to the edge of the water to, I thought, get a closer look, sit on the low wall next to the water, and watch the birds. I was wrong. Every single one of them pulled out his/her cell phone or point and shoot camera and pointed it at the birds and made what could only have been the world’s most banal photographs of birds in water. I don’t recall a single one of them watching and experiencing the actual birds rather than recording the event for, well, for what exactly? “We went to San Francisco. There were some birds in the water.”

I often see a related form of photographic dysfunction when I’m making nature or landscape photographs. I might have found a beautiful spot, looked at it and studied in long enough to find a composition, and set up my camera to wait for the light or clouds or for the wind to stop. Or I might not yet have found a shot, instead just looking and walking around the scene, taking in its visual nature, thinking about color and light and wind and texture and form, waiting to see a photograph. If I am anywhere near a road, almost invariably one or more cars will pull up, windows will be rolled down, cameras poked through windows, windows rolled up, and away goes the car. Sometimes they don’t even slow down to make the photograph, driving by at the speed limit with cameras pointed out the window!

I cannot deny that there is some value in using a camera to simply record proof that you were there, and I’ll admit that I enjoy seeing old family photographs of people in these places. But the reflexive action of photographing everything at the cost of experiencing nothing seems sad and a bit perverse to me. If this thing being photographed is so special that it is worth traveling great distances to see it, isn’t it also worth slowing down long enough to experience it and take it in through all of your senses? Isn’t it better to experience five things deeply than to skim the forgettable surface of 100 things without pausing?

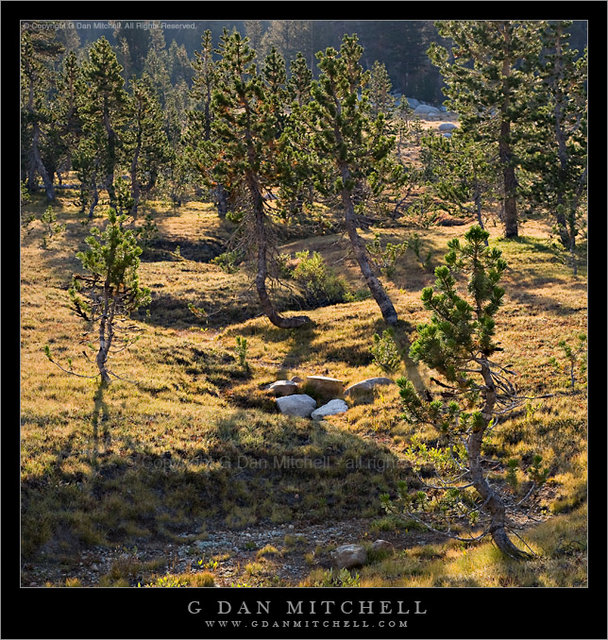

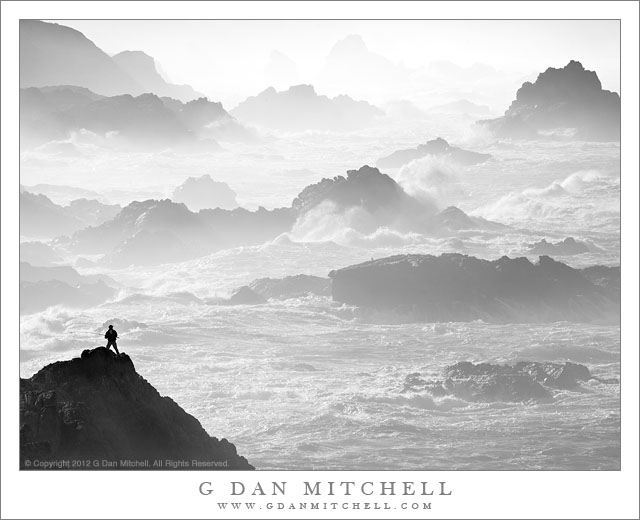

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | 500px.com | LinkedIn | Email

Text, photographs, and other media are © Copyright G Dan Mitchell (or others when indicated) and are not in the public domain and may not be used on websites, blogs, or in other media without advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.

Like this:

Like Loading...