(“A Photograph Exposed” is a series exploring some of my photographs in greater detail.)

On the weekend of June 18-19 of this year I made a point of getting to Yosemite so that I could photograph the high country on the first day that Tioga Pass Road was open for the season. On a shoot like this, my subjects range from some that I planned to shoot ahead of time to some that were completely unanticipated. Among the many things that might affect my decisions is the light itself, and this is a story about that light… and perhaps a few other things, too.

I had driven to the park very early on Saturday morning and after photographing straight through the morning I finally made it over the pass and headed down to Lee Vining Canyon to find a campsite for that night. After getting up at 3:30 a.m. and driving to the Sierra from the SF Bay Area and then shooting all morning, I was exhausted! I pulled into the first available site, paid my fee, and promptly fell asleep in the car for perhaps an hour. When I woke up I set up my camp and at about 3:00 or so headed down to Lee Vining to get some “dinner” – on “photographer time,” dinner tends to either be very early or very late, and on this day I made it early so that I could be back up in the park well before the “good light” started.

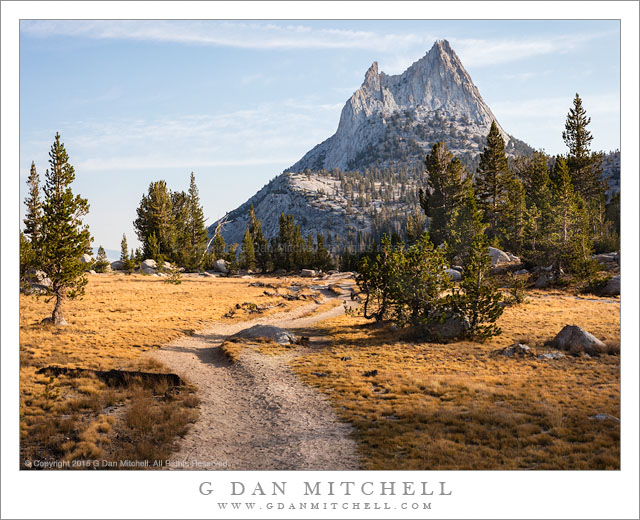

Heading back up to Tioga Pass after my mid-afternoon dinner, I had a few subject ideas in mind. Tuolumne Meadows itself was one possibility, and I knew that I wanted to watch for any cascades or creeks that would be flowing in the spring snow-melt conditions. Tenaya Lake was another possibility, and a client’s interest in photographs of Mount Conness had me thinking about the possibility of a photograph from Olmsted Point that included ice-covered Tenaya Lake and this peak. Continue reading A Photograph Exposed: A Tale of Light