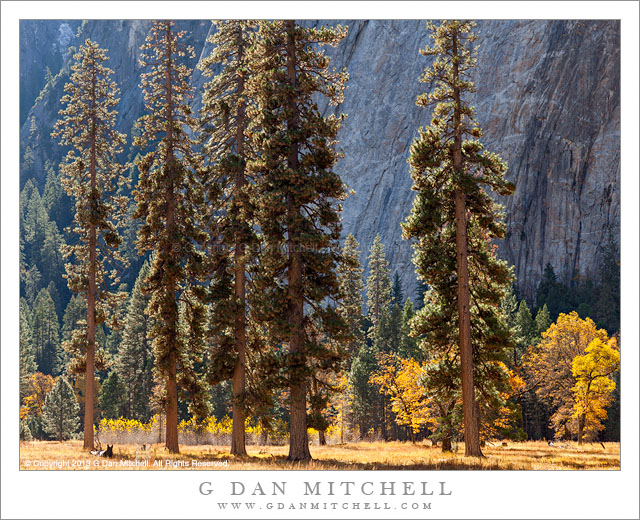

Tall Trees, Meadow, Autumn. Yosemite Valley, California. October 30, 2013. © Copyright 2013 G Dan Mitchell – all rights reserved.

Tall trees grow in a row in a meadow backed by cottonwood and black oak trees with autumn foliage

I guess I just can’t help myself when it comes to photographing in this Yosemite Valley meadow area – or in similar areas, for that matter. As I’ve written before, during the time of the year when the days are shorter and the sun is lower, the light in some of these places is constantly changing – pre-sunrise and post-sunset soft “blue hour” light, early and late direct sun over the upper edges of cliffs, shadow right after dawn and before sunset and when cliffs interrupt the light during midday hours. Other changes take place on a longer cycle – the stark quality of winter, snow covering everything when winter storms arrive, morning fog, trees newly green in spring or yellow and gold in fall. And there are many more things to see than just the “landscape size” things – wildflowers, fallen leaves, frost, and more.

So, yes, I visited and revisited the meadows during this fall’s end-of-October visit to The Valley. While I often focus on the black oaks that grow in these meadows, here I decided to focus on evergreen trees. This group stands almost evenly spaced in a row. I struggled with how to deal with their height when shooting from a relatively close distance, and then realized that by not including the whole tree I could emphasize the vertical lines of their trunks and perhaps suggest the even higher parts of the trees that are not visible here.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | 500px.com | LinkedIn | Email

Text, photographs, and other media are © Copyright G Dan Mitchell (or others when indicated) and are not in the public domain and may not be used on websites, blogs, or in other media without advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.