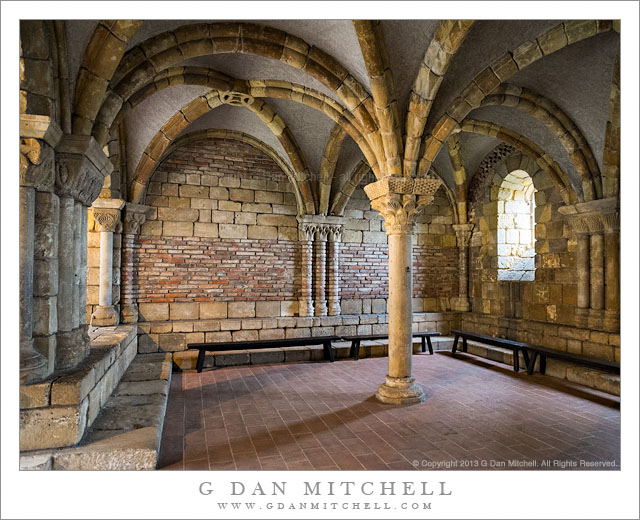

The Cloisters. New York City. December 30, 2013. © Copyright 2014 G Dan Mitchell – all rights reserved.

Large stone room at the Cloisters museum, Tryon Park, New York City

The Cloisters is a facility that is a (remote) part of New York’s Metropolitan Museum, located way uptown at Fort Tryon along the Hudson River not too far from the George Washington Bridge. It was constructed as a sort of showplace for various elements from early European architecture and art, and it feels far removed from much of the rest of the New York experience, at least to this Californian. We had visited, or tried to visit, on a previous trip to New York, going all the way up there only to find that we had picked the one day each week when it was closed! So getting back there and going inside was on our agenda during our late 2013 visit.

The weather and light affect my response to such places, and this was a gray winter day. We took the subway up from lower Manhattan, and when we got off at Fort Tryon it was very cold, very gray, and quite windy as we walked to the Cloisters. Once inside, the light coming in from courtyards and windows was soft and diffused, and I thought the light in this room was especially beautiful. Some light was coming in from outside through the small window at the right, but out of the frame to the left there is a large open courtyard that was also spilling light in from that direction.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

G Dan Mitchell is a California photographer and visual opportunist whose subjects include the Pacific coast, redwood forests, central California oak/grasslands, the Sierra Nevada, California deserts, urban landscapes, night photography, and more.

Blog | About | Flickr | Twitter | Facebook | Google+ | 500px.com | LinkedIn | Email

Text, photographs, and other media are © Copyright G Dan Mitchell (or others when indicated) and are not in the public domain and may not be used on websites, blogs, or in other media without advance permission from G Dan Mitchell.